From Awareness to Action: Siddhant Shah on Rewriting Accessibility in the Arts

01 | 12 | 25

Written by Tina Wadhawa

Siddhant Shah, founder of Access For ALL, has spent the past decade rethinking how cultural spaces define and implement inclusion. His work focuses on creating environments where audiences with diverse physical, sensory, and social backgrounds can experience art with autonomy and dignity. For Shah, accessibility is not a symbolic gesture or a branding statement; it must be embedded in the way art is presented, understood, and cared for.

We sat down with him to discuss the evolution of accessibility in the arts, and the practical ways festivals, galleries, and artists can make their work truly inclusive.

Q.1. How did your early experiences with accessibility shape both your perspective and the vision behind Access For ALL?

Shah’s path to accessibility work began in deeply personal circumstances. While studying architecture, his mother acquired a visual impairment, fundamentally reshaping his perception of public spaces. Around the same time, a UNESCO and ASI competition invited him and two friends (Jay Kapadia & Siddhi Desai) to envision ways to make a world heritage site accessible. “We had no clue what it even meant at the time,” he recalls, yet the project culminated in a hands-on experience at Sanchi Stupa, designing spaces for children with diverse abilities. The experience highlighted the practical and ethical complexities of inclusion, setting the tone for Shah’s future work.

Another formative experience came in an unexpected and uncomfortable setting. During a visit to a Mumbai art gallery, staff politely asked Shah and his mother to leave, concerned she might touch the artworks. The moment underscored the persistent invisibility of accessibility in cultural spaces.

Q.2. Accessibility is often treated as a buzzword today – what do you wish more institutions understood about its true scope?

As Access For ALL marks a decade of work, Shah reflects on the evolving clarity of the organisation’s mission – moving firmly “from awareness to action.” In a cultural landscape where accessibility has become a popular talking point, he notes that the term is often used without acknowledging its true breadth. Accessibility, for Shah, goes far beyond disability inclusion; it calls for equitable access across social, economic, religious and cultural differences. This wider lens continues to guide how Access For ALL defines its role in reshaping who feels seen, welcomed and represented in art spaces.

Rohan Marathe, Karishma Das and Siddhant Shah

Q.3. You often say accessibility must be embedded in every decision — what does it look like when inclusion is part of the entire visitor journey in art spaces, not just the programming?

When Shah is asked what it truly takes to make an art space accessible, he makes it clear that inclusion cannot sit on the margins of planning. It has to be present in every decision that shapes an experience. He begins with transparency: a thorough accessibility audit that is made available online so visitors know before they arrive how the space will support them and which areas might be difficult to navigate. He draws attention to neurodiverse audiences too, who often encounter strobe lighting, disorienting transitions, or intense environments at art festivals and fairs. Clear descriptions and the presence of sensory or quiet zones can transform these settings into places of ease.

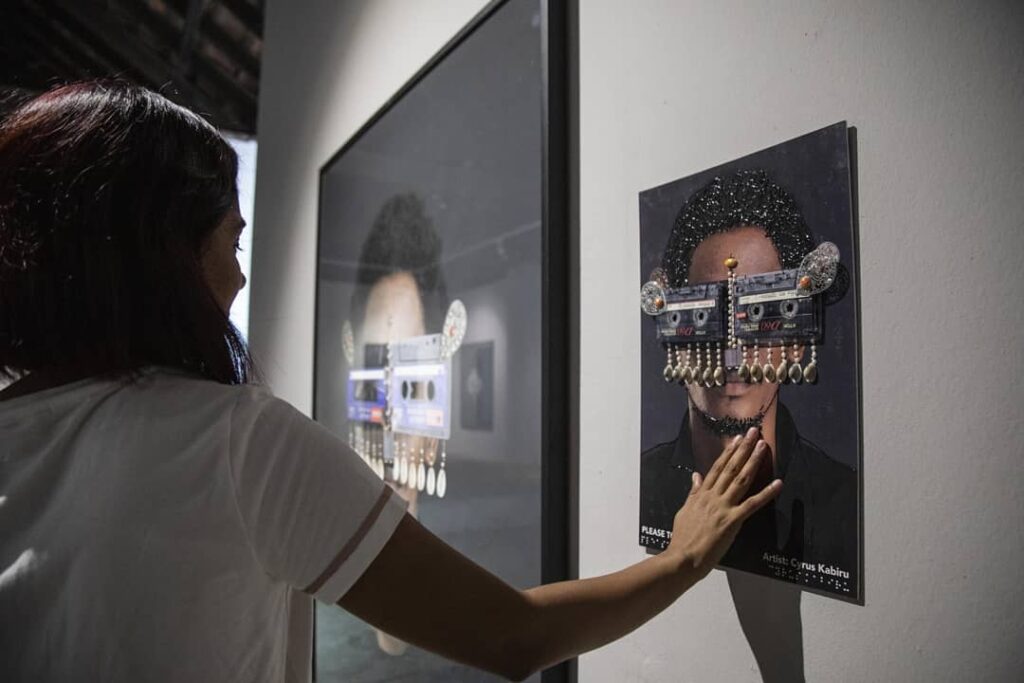

He also highlights that accessibility is about the entire journey, not just the programmed moments. If a panel offers sign language interpretation, it should begin at the information desk, the very first point of contact for Deaf or hard of hearing visitors. Touch-based engagement is another priority. Tactile artworks and Braille captions do more than provide access to visually impaired audiences. They invite curiosity, allow children to learn through touch, and challenge the idea that art must remain distant.

Above everything, Shah argues that the most meaningful shift happens behind the scenes. “If you have people with disabilities on your team, your event automatically becomes accessible.” Their lived understanding pushes organisations beyond symbolic gestures and toward real accountability, ensuring that inclusion is not a checklist but a culture.

Q.4. How can artists thoughtfully weave accessibility into their work to create richer, more inclusive experiences for all audiences?

Shah’s vision extends to artists themselves. Through workshops in collaboration with Chennai Photo Biennale and the British Council, he has guided creators on how to make their work approachable for diverse audiences. Small interventions – tactile elements, magnified sections for low-vision visitors, or scaled-down interactive components – can transform how audiences engage with art. “Accessibility is incremental,” Shah notes. “You don’t have to make everything fully accessible immediately. Small steps make your work more special and available to all.”

By embedding accessibility in the work itself, artists cultivate deeper connections with their audiences. Material choices, interactive installations, and inclusive storytelling can all create more welcoming spaces for engagement.

Q.5. How have you seen accessibility evolve from being treated as a separate add-on to becoming integrated into mainstream exhibition design and programming?

Reflecting on a decade of work, Shah has witnessed the art world’s understanding of accessibility move from symbolic gestures to more integrated change. In the early years, Access For ALL was often assigned a corner or a designated zone where accessibility could be “added on” through tactile displays or outreach workshops. The intention was present, but the approach positioned inclusion as something separate from the mainstream experience. Over time, major cultural platforms have begun shifting that perspective. Shah points to Serendipity Arts Festival, India Art Fair, and institutions such as KNMA and DAG as leaders who are weaving accessibility into the structure of their programming and exhibition design.

Today, visitors are more likely to encounter tactile interpretations placed within the main exhibition space or see inclusive events featured within the regular schedule rather than siloed for specialised audiences. This shift in visibility and parity signals a broader cultural change. “We are at the cusp of our 10th year and now looking at the different ways in which we would like to go ahead,” he notes, acknowledging both the progress made and the work that remains. For Shah, accessibility in the arts has entered a new phase, one where true inclusion is measured not by what is added on but by what is built in from the very beginning.

Q.6. What comes next for Access For ALL in ensuring accessibility moves from intention to a sustained, universal practice?

Standing at the threshold of a milestone year, Shah sees Access For ALL entering a moment of renewed purpose. A decade of fieldwork has revealed both how far the discourse on accessibility has come and how much still needs to evolve. Looking ahead, he envisions growth in two key directions. The first is outward, toward geographies that share structural and cultural similarities with India. Countries across Africa and Southeast Asia are also grappling with how to embed inclusion within the creative sector, often without established frameworks or institutional support. Shah believes that the knowledge Access For ALL has accumulated can become a resource for these communities, offering not prescriptive solutions but collaborative pathways that are shaped by local contexts.

The second direction is one of scale and adaptability. Shah wants to move beyond bespoke interventions designed only for museums and art festivals. He imagines accessibility as a format rather than a feature, something that can be installed, replicated, and customised. Schools, hospitals, and corporate workplaces all stand to benefit from environments that recognise the diverse needs of the people who inhabit them daily. Toolkits that are easy to integrate could help close the gap between awareness and actual change, making inclusivity an everyday standard rather than an exception.

“We are now looking at the different ways in which we would like to go ahead,” Shah notes, reflecting the careful ambition of a team that has learned to innovate with integrity. For him, the next chapter is about building systems that sustain inclusion long after a festival ends or an exhibition closes. It is about shattering lingering illusions that accessibility is a specialised concern and instead proving that it belongs everywhere. As Access For ALL steps into its tenth year, it carries forward a mission that has only grown sharper and more urgent: to turn intention into action and ensure that art spaces truly welcome the world that surrounds them.

Interview by Nyrika Bose.

All images courtesy of Siddhant Shah.