With the shadow of an unseen virus looming over us, making us confined within the static contours of our home, we seem to have been gripped by a prolonged sense of the present. We’re mugging up our routine daily by gulping down our throat the constant reminder to social distance. It is in the spirit of being apart physically but never alone, that we are moving towards an ecology of solidarity and community as opposed to our individualized existence currently grimacing at the collapse of the economy. This sudden halt from our speedy lives has made us rethink our choices, reevaluate our connections and has opened our eyes to the white noise that is our mortality and transience ticking away to glory.

On that note, Shrine Empire’s online exhibition ‘Speculations on a New World Order’ curated by Anuska Rajendran, attempts to meditate on the imminent changes that will transpire as a consequence of this post-pandemic dystopia. It brings together possibilities imagined by ten distinct artists who contemplate in their own singular ways the alternative futures that can be anticipated. The exhibition which has been conceived for online viewing also interrogates the truism that assumes physical encounter with an artwork as fundamental to the experience of art.

We are lucky to have had the opportunity to engage in a conversation with three of the artists displaying at the show who elucidated on their fascinating approach to art, their practice and the concepts that informed their vision and helped materialize into their respective features on the show.

Afrah Shafiq

One of the artists showcasing their work at the ongoing online show is Goa-based artist Afrah Shafiq, who tells us why she feels it is imperative to talk about the many unheard narratives of female identity, all of which are pivotal in the making of her work ‘now-where’ (2020) featured at the show.

1. What has inspired you to take up the question of female identity built upon a woman’s relationship with her domestic world?

I am interested in the inner lives of women and the domestic space is a large part of their daily existence. No matter what part of the world we look at and largely across time it is the home and its linkages that take up most space in women’s lives – mentally, physically, time wise, in relation to the self as well… the domestic world is both at the same time very present in women’s lives and yet quite under represented as an exploratory space in popular culture. I feel quite drawn to unearth that.

2. Could you comment on how you see the differences that have come about in navigating one’s womanhood between present day and the late colonial period considering her access to the world beyond home?

A lot has changed, sure. Women have more access to the public space. They increasingly have a presence in fields where it was unheard of for women to enter, and yet in some sense nothing has changed. In most homes, domestic work is automatically thought of as “women’s work”. Their partners might “share the load” but that’s also a problem right, they only share and help women with their work. They don’t look at it as their own work too. Sometimes I catch myself really paying careful attention to women when they are at work in the home. I like listening to what different women have had to say about it through time. Everyone undervalues housework, including women. I have so many times heard women who keep house say apologetically “nothing” if they are asked what it is that they do. Of course, questioning this mindset is nothing new. Angela Davis’ writing in “The Approaching Obsolescence of Housework” is an important one for instance. Feminists for generations before me have been engaging with the idea of domestic labour being just that, labour; about the unpaid, unacknowledged nature of it … but domestic labour is also repetitive and endless and does not always need to use the cognitive brain in a very present way. There can be something very meditative about it; something quite hypnotic and trance-inducing about using the body in this cyclical manner. So I think of all these women doing their domestic work entering a state of a mechanized being – almost as if they are morphing into machines. And while their bodies are physically present inside the walls of the home, cutting or washing or sewing, where do their minds travel?

3. How do you translate the transgressive potential of a woman’s household chores into your practice?

In ‘st.itch’, a past work that I made based on research from archives in the North of England, I kept feeling drawn to these images of women making my hand, sitting indoors in their “free time”. Sewing, lacemaking, knitting, embroidery, weaving… such things are often looked at as a cute decorative time pass stuff done by women. But as I kept exploring I began speculating connections between these acts and cybernetics, computer programming, code, machine automation, and the world of the Interweb. I looked at so many cross-stitch hankies called samplers sewn by young girls in England and all of them looked like early computer pixel graphics. We all know that Charles Babbage made the first computer, but it was also Ada Lovelace who wrote the programme or the code for it. She got the idea from the Jacquard Loom that weavers used. Weaving follows a binary code logic, just like computer code. If you look at the notes made by “pattern girls” who were employed in the Manchester cotton mills, they are nothing short of complex formulaic codes. Knitting too is in many ways like building a formula in your mind. A weft and weave arranged in different combinations will generate different patterns much like the logic of the dataset and ones and zeros in binary codes. Surely all of this cannot be a coincidence?

Sharbendu De

Sharbendu De is a Delhi-based photographer and academic, presently teaching photography and Visual Arts at Jamia Millia Islamia University and Sri Aurobindo Centre for Art and Communication, both in New Delhi. In our interview with him, he opened up about the inspiration driving his artistic practice, his exhibits at the show ‘Speculations on a New World Order’ and much more.

1. For the current show ‘Speculations on a New World Order’, what are the symbolic tropes you have used to envision a post-climate-crisis dystopian future?

Concerned by issues of climate change, environmental degradation and rapid destruction of our ecology, in 2016, I instinctively embarked on creating ‘An Elegy for Ecology’ which is currently part of the online show ‘Speculations on a New World Order’.

It narrates the loss of habitat, loneliness and man’s quest for survival — set in a dystopian future caused due to climate catastrophic factors. Atmospheric temperature has risen abnormally thus leading to drying up of water bodies and accelerated extinction of floral and faunal species, and oxygen in the Earth’s atmosphere has depleted to unsustainable levels. How will we survive, then? Look at the global air pollution index including Delhi where we battle with smog and alarming AQI levels, annually. Many have died of respiratory illnesses. Our extinction is fait accompli.

The directed mise-en-scènes in my series envisions how we might be coping with such a future. I do this by depicting domestic spaces inundated by trees (beyond the aesthetic function they perform in our houses today) to generate oxygen. Trees and animals — prized commodities — have overtaken private spaces and clean oxygen has entered the commerce of human relationships. For example, in the image An Elegy for Ecology – 2, we see a couple in their bedroom staring in different directions, each engrossed with their respective breathing apparatuses. Despite this being an intimate scene unfolding between the couple, the overall cold tonality and the overwhelming amount of trees, after a point, gets disturbing.

So, I have taken a symbolic route to tap into the collective unconscious, instead of a mimetic one. The signifiers in each frame in this ongoing series are, semiotically speaking, allusions, not statements. They require interpretation.

Symbolic tropes like — oxygen-helmets, domestic spaces inundated with plants, white swan, black cat, white rabbit, caged birds and three Fighter-fishes in a tiny fish bowl — recur in these everyday domestic scenes, as well as archetypal relationships between men and women. The contrasting colour palettes and their interplay is meant to further build and heighten the mood whereas the near documentary cityscapes and external landscapes intensifies that other-worldly feeling that ‘something outside is not right’.

2. As a critique of the Anthropocene and a hyper-capitalistic reality, why have you chosen an approach that is quite mythical owing to its high poeticism to portray such a morbid picture?

Artistically focused on evoking feelings in the viewers’ imagination, I simultaneously deal with our real-life collective concerns of the future. The subject is morbid, indeed. But who determines how morbid stories are to be told? Where was the rule set that morbid topics can only be dealt within the ambit of a specific treatment? Remember Life of Pi’s (Dir. Ang Lee; 2012) alternate ending scene? The Late actor Irrfan Khan as the adult Pi Patel asks the Writer, “I’ve told you two stories about what happened out on the ocean. Neither explains what caused the sinking of the ship, and no one can prove which story is true and which is not. In both stories, the ship sinks, my family dies, and I suffer. So which story do you prefer?” The Writer replies, “The story with the tiger. That’s the better story,” to which Mr. Khan quips, “Thank you. And so it goes with God.” Life of Pi is an allusion to address a question without serving readymade answers.

Storytelling can take diverse forms and approaches. I took the symbolic one. In ‘Psychology of the Unconscious,’ Carl G. Jung wrote, ‘symbolism and mythology are the natural languages of the unconscious’*2.

In a postmodern post-truth world, interests of ‘I’ has taken over concerns of ‘We’. And collectively, we have become harsh and indifferent as an act of self-preservation. This problem is further exacerbated by a daily overdose of infinitesimally similar looking images, which mostly imitates as well as amplifies the reality of the known world (hinging on shock, sensationalism and exploitation), but seldom replaces it with a reality of its own. Oversaturated by mimetic imagery and compassion fatigue, we treat them as objects for consumption, or records of events occurring in distant lands. Without presenting an alternate interpretative reality, will we, as storytellers, be able to break this great wall of human apathy? I seriously doubt.

On the usage of animals and nature as signifier, I have for long been allured by the mythical relationship between man-animal and nature as a metaphor, evinced in my works Between Grief and Nothing (2015-16), Imagined Homeland (2013-19) as well as An Elegy for Ecology (2016-). John Berger, in his remarkable essay ‘Why Look at Animals?’*3 part of the anthology About Looking wrote, ’If the first metaphor was animal, it was because the essential relation between man and animal was metaphoric. With their parallel lives, animals offer man a companionship which is different from any offered by human exchange. Different because it is a companionship offered to the loneliness of man as a species’.

The discussed series, then, I believe, portrays an alternate reality to represent the same morbid reality. But the ache might emerge only if the viewer allows the symbolic elements in these images to osmotically seep in. Frankly speaking, the actual message or meaning (if any) of this series, resides not within its confines, but elsewhere. What is more important— the photographic medium and our storytelling approach, or to place a question that compels us to think and, as a result, engage with the story?

3. How do you address environmental collapse as a consequence of capitalism and

industrialism in keeping with your allegiance to images which are some of the most

saturated commodities of consumer culture?

I do not have a ready-made formula at my end. Like many of us, I am also searching for a way to use visuals to confront human and institutional apathy towards issues of environmental degradation, climate change and so on. I am acutely aware of the over saturation of images in this commodified consumerist society, and as an initiating note, I have refrained from creating more mimetic works to pour into that black hole of images. Instead, I work slow, with colours, my frames are layered and coded with the meaning at times eluding the frames. A major part of my working time is now consumed by research and reading. Slowing down is very important. But allow me to add a parting admission – my allegiance is not to images; it is to the story and to the art of (visual) storytelling.

Citations:

*1 https://www.desharbendu.com/between-grief-and-nothing-1

*2 Jung, C. G., The Red Book: Liber Novus, ed. Shamdasani, Sonu, tr. Peck, John, Kyburz,

Mark, and Shamdasani, Sonu (WW Norton & Co., 2009)

*3 http://artsites.ucsc.edu/faculty/gustafson/FILM%20161.F08/readings/berger.animals%202.pdf

Bhagwati Prasad

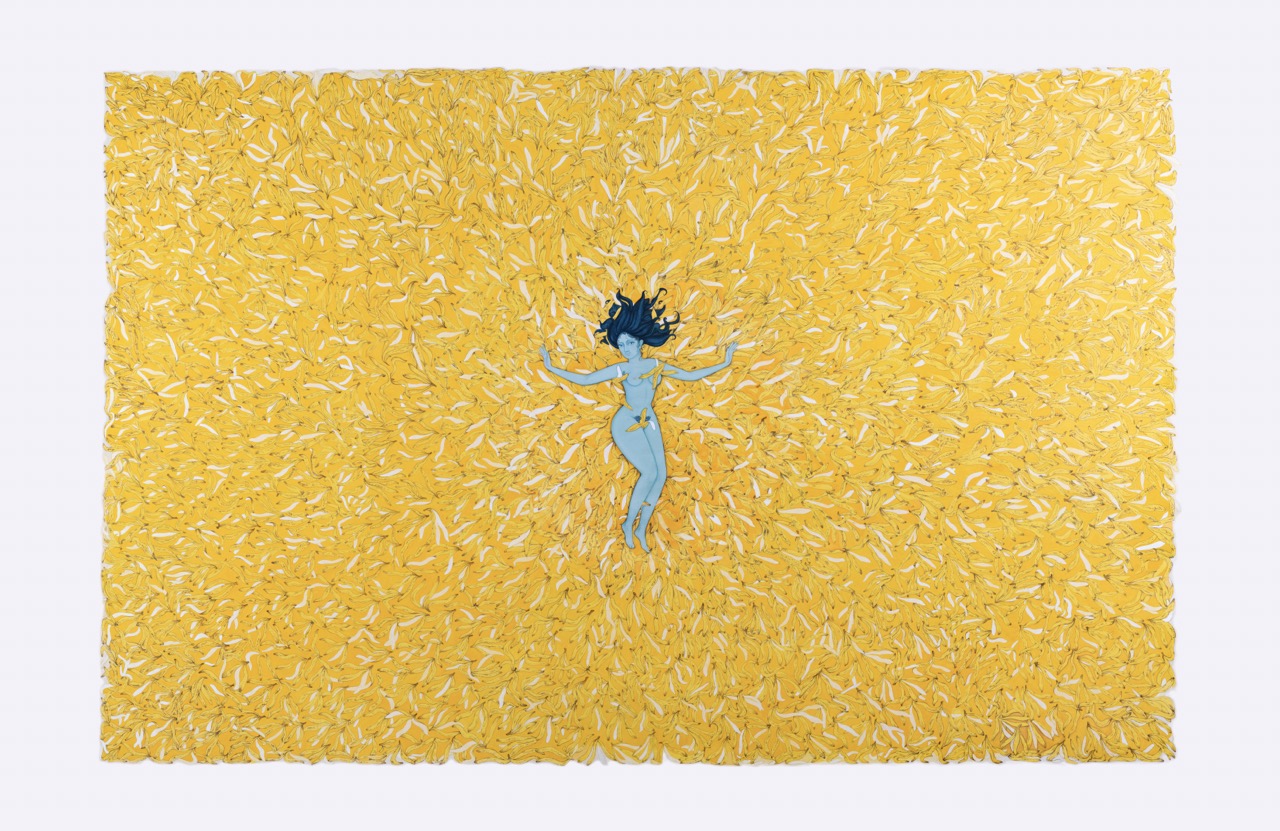

Last but not the least, we get a sneak peek into the ideas that led Delhi-based artist and researcher Bhagwati Prasad to embark on his new series ‘Begumpura’. He is also known to have worked in varied mediums including graphics, performance, sculpture and video.

1. For your series called ‘Begumpura’ which translates as a place without sorrow where all hierarchies are erased, can it be imagined as a heterotopia?

There is a beauty in the multiplicity of places being in juxtaposition that makes Heterotopias. But the important thing is a discussion to look carefully at the making of places, their protocols of opening and closure, and mutual acceptance of difference without hierarchy. Begumpura in one sense is a place, but, more than a physical place, it is a decision to challenge thought about a place. Begumpura is everywhere and yet nowhere. It is in everyone and appears in every life. The struggle is to accept it within ourselves, and with each other.

2. What has inspired you to materialize this series which celebrates life in general, where all ecologies collide and coalesce to give rise to endless possibilities?

Each entity is a transforming agent. To change the way we live we need to start from an affirmation of something we all, individually and collectively, do well. To take the human, for example, the Constitution shows that somewhere we all have accepted equality as a value and a decision. That is a radiant starting point. To extend, grow, and merge with the joy of being equal. It can become mundane, a habit, from repeated practice and telling. It has the power to transform our worlds. Millions of entities—living and non-living—are part of this.

3. How important do you think is this egalitarian imaginary of saint Ravidas considering the regimented and discriminatory times we are living in?

Shailendra wrote in the 50s – “If there is heaven bring it down amidst us”. But he deferred its coming. Saint Ravidas gave Begumpura not a delayed, deferred presence. To him it is all around. We have to understand this profound insight. It is a sense that we are all in, all the time. The crucial thing is to sense it. To live it. Not to let it be obscured by hierarchical and discriminatory habits.

The online exhibition organized by Shrine Empire is on view until the 20th of May. We are most delighted to have been able to get an in-depth understanding of the thought behind this show, and have gained a lot of insight from our tete-a-tete with the artists who enlightened us about the multiple facets of art as both theory and practice. We look forward to building more such enriching relationships with galleries and artists through our interviews. If you liked reading this, you can look up our past blogs such as this on our website!