“To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge- and therefore, like power.”

- Susan Sontag

Lately, it has become difficult to steer our attention away from the news channels and social media feed as the death tolls rise due to Covid-19 all over the country and the frequent volatile clashes among interfaith communities stirred by the ongoing elections in West Bengal. Scrolling through images and videos of patients in distress during lunch breaks, have we paused to glance at the photojournalists behind these images, the larger role they play and the repercussions caused by their visual documentations?

A photographer with a camera has always been much more than a mere passive witness to events of beauty and horror. Surpassing its role as a capturer of memories, evidence and a visual art form; photography has also been employed as an instrument by nations and institutions in power. As implied by late photographer Susan Sontag, photographers consciously create a corpus of knowledge through their images that at times act as the proof of a reality and agents of a dominant narrative.

Since the time of its introduction to the undivided Indian subcontinent, photography has acted as a bridge for cultural exchanges between the citizens of the country and the colonial rulers. The photographic practice began during the zenith of the British colonial period. Over time, the camera evolved from an instrument of visual storytelling to a method of administering and dominating over a vast, divergent population.

After the invention of cameras in Britain and France, the appearance of photography in India was almost immediate. In the 1850s as British colonies increased in numbers, a large number of photographers visited India to capture the architectural, natural and anthropological elements of the country. This led to the cognitive exchange between British photographers involving the transfer of their skills to native Indian draftsmen and surveyors, strengthening the use of photography as an administrative tool. The camera entered as an instrument to document people, traditions, monuments and notable events.

While the expeditions of these British photographers across the subcontinent were regarded as an endeavor to document and record the momentous events, changing landscape and the socio-political scenario, there are several underlying narratives that counter this glorification surrounding the imperial era and the advancements it brought.

Inception of Photography in 19th century India

By 1860-65, every city with a British administration had several studios. The three presidencies of that period i.e. Bombay, Kolkata and Madras were the first metropolises to host these commercial photography studios. One of the first and principal initiatives among these was the Bombay Photographic Society (October 1854). Established by Governor Lord Elphinstone and Lady Canning, it started with over two hundred members hailing from diverse professional backgrounds. The Bombay Photographic Society and its monthly journal became a successful platform for the exchange of knowledge between local amateurs and expert practitioners. Photographers like Raja Deen Dayal, Hurricund Chintamon, Samuel Bourne, Charles Shepherd, Linnaeus Tripe, Willoughby Wallace Hooper Henderson and Johnson, Underwood and Underwood set out on trips and captured images of the architectural wonders, unusual topography, portraiture of royal families and indigenous ethnic communities. Their photographs trace the eccentricity of India’s customs, the grandeur of royalty, festivities and architecture, all at its best.

The relevance and significance of their images is evident in their portrayal of a visual narrative of changing cultural and actual landscapes during 19th century India. From town planning and building heritage sites to the mountain regions and the ethnic communities and their way of living, these images provide an overview of India. Their photographs were not simply a reflection of the architectural and cultural landscapes, but gave us a glimpse of the perspective through which the British saw India and its inhabitants. They also played an important role in depicting British ideas about Indian society. Photography began flourishing both as a medium of artistic expression and as an administrative tool.

The Camera as a Tool of Subjugation

Behind the grandeur and historical importance of these photographs as priceless carriers of documentation, we cannot overlook the underlying intentions behind these photographers. Like several English travelers of that time, the renowned British photographers were caught up with the exotic and romantic sensibility surrounding India as a colony and its ‘sweeping, picturesque landscapes’.

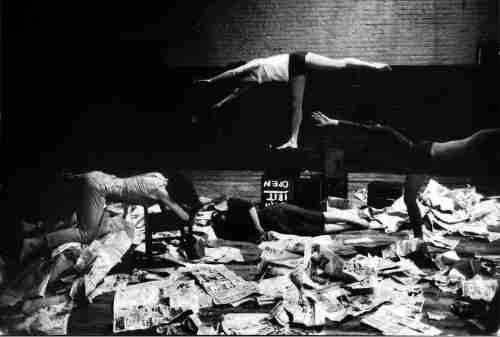

However, in the process of documentation they tended to bypass the ethics of photojournalism. As pointed out by writers Diva Gujral and Nathaniel Gaskell in regard to their collaborative book “Photography in India: A Visual from the 1850s to the Present” some photographs, especially those of the members of indigenous ethnic communities remain witness of the coercion employed to capture them within their native environments; where these subjects appear visibly uncomfortable in front of the camera. Images like these hint at the larger processes of subjugation and control that were not allowed to come to the surface.

The disparity in the photojournalistic practices of British photographers and Indian photographers is quite distinct here. The difference lies in the subject in their photographs and the outlook through which these protagonists were captured. Samuel Bourne, Linnaeus Tripe, William Johnson were driven to document and record the primitive cultural landscape of the country, the tribal communities and working class, ignoring the sensibilities regarding their subjects. Besides their enthusiasm towards photography, their agenda appeared to portray the “chaotic and primitive East”; in desperate need of colonial intervention through images of famine stricken villagers, racial stereotypes, dilapidated buildings and heritage sites and the impoverished labour class.

Though their images provide a realistic visual testimony of the economic scenario of 19th century India, they are devoid of the cultural sentiments and inclusion of consent from the human subjects in them. And in case of landscape photography, the visual aesthetics was one of order and stability. Rather than depicting remote regions as untamed or untouched, the photographers tended to highlight the mountains, sweeping valleys and tropical flora and the establishments of affluent English bungalows.

The narrative being depicted through the documentation by British photographers can be construed as the legitimization of the colonial presence. Although these images when published in newspapers of Great Britain they ultimately sparked serious controversies over the function of the British empire and the administrators posted in India. The photographs were indicative of the highest kind of colonial cruelty and mismanagement. The debate regarding the need of a British colonial power in India spread throughout the higher echelons of the British government.

Locating the Neutral Grounds

Despite the political undertones and the larger administrative processes involved with photography, colonial India’s early cameras were also used to produce art, postcards and souvenirs. Some of the first images to be captured in the country were taken by the British army and civil service to ease the process of record-keeping. A camera had the capability to replace a team of draftsmen who were employed to document the planning and layout of buildings.

Keeping aside the underlying visual narrative and power struggle implied by the British photographers by their documentations 19th and early 20th century India, their works are crucial to the study of colonial history for scholars and researchers. Their significance spans beyond their sole function as records; they are testimonies to the impact of the colonial empire and the employment of photography to serve as proofs of historic moments and the socio-cultural transformations.

The British empire and its atrocities had sparked a zeal among several artists of 19th century India to rebel through their creative practices. Take a short break from work and the news and read all about these Indian artists who remain integral to the freedom struggle here.