The seeds of Islamic Art were sown in the interactions between empires situated in remote territories with a closer spiritual position. One such seed lay on the expanse of the Mughal empire, where the heart of miniature paintings on preserved surfaces would have been absent without Emperor Humayun’s experiences during his exile in Persia. His fascination with the Persian art form was realised when he brought with him two Persian painters, Khwaja Abdus Samad and Mir Sayyid Ali, upon his return in the 16th century, as they used their vision to nurture the unimaginable with watercolours and gold leaf.

While power saddled the heritage of various dynasties that represented Islam, it was etched in time by the iconic for pairing of canvas and quill. From minarets and miniatures to paradise and penned histories in a universal visual language, Islamic art has remained eternal, not only as the expression of a way of life, but also as a subject of immense value to those who witnessed its conception then and those who witness its grandeur now.

November 18, the occasion of International Day of Islamic Art, is a celebration of its legacy – one that is shared by territories across the world that once belonged to its dynasties and those who resurrect its historical marvel in the contemporary world. It is a day quite fit to observe like its artists did, appreciate as its then spectators did and trace its influence like its present audience does.

Here are a few contemporary instances reminiscing Islamic art and its shade on the history of creative calibre amidst the empires led by it!

The Book of the Moon

Accompanied by the role of a talisman’s belonging, artist Joumana Medlej’s The Book of the Moon is a portable version of celestial power, time and a guide to the lost. With the role of calligraphy in the larger body of her works, she looks to religious narratives and roots to discover the importance of her visual conscience translated for the present-day spectator.

Its shape, as a complete circle, takes each fragment to represent the twenty-eight phases of the moon, along with the mansions or “manazil” formed by the group of stars and zodiac signs that are of close relevance to the fate of the night.

Medlej chose to create this work in an edition of only fourteen, going by the number’s connection with the moon. The inspiration, however, came from medieval Islamic astronomical charts and the visual language that dominates the role of scientific and religious inquiry.

With the interest of being deciphered, Medlej’s thoughts are consistent with the accuracy in the constellations and the manner in which each layer is crafted. One cannot miss the visible consequences of a deep research bound by four early scripts on each of the layers. A purpose behind the work is left undefined, for it could mean different things for different people, as they hold the same sight on the moon, which could be writing their destiny in the night sky.

The Wall-Dome

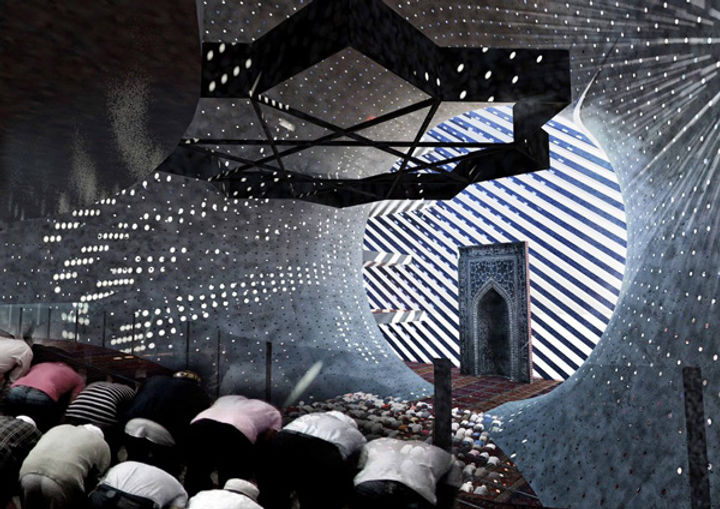

Bulevardi Dëshmorët e Kombit in Prishtina is an urban icon of religion that brings together tradition and modernity through architectural expression. Its foundation is of symmetrical as well as religious significance, with regard to how its attendants in the community face the direction of Mecca while praying. In order to develop a relationship between the divine and the worshipper, it not only addresses the role of a mosque, but also includes areas for cultural and educational interactions.

The dome was planned with several levels to keep the rituals of a mosque intact as it embraces all faithfuls and tourists with environmental and climatic consciousness. It is not only a location of unified spiritual exchange, but also captures an energy system for the greater benefit of both humans and nature. The sunlight gleaming from every end realises the traditional means of recognising day and night, particularly through sunrise and sunset.

Architects Paolo Venturella, Angelo Balducci, Luca Ponsi and Paolo Gaeta brought forth their experiences in the form of louvers, which are occupied by sustainability. The monolith provides for religious and cultural ceremonies, ornamented by natural and photovoltaic ventilation, inviting nature to be a part of humankind.

A circular build houses indirect rays of sunlight, thus giving the insiders a glimpse of the outside world while maintaining the mosque as a sacred space within and without it. The durability that the mosque is made of is also reflected equally in the Kibrah Wall inside it, as it opens the gateway to the religious paradise of Islam.

Syed Muhammad Khayyam Shah’s Ode

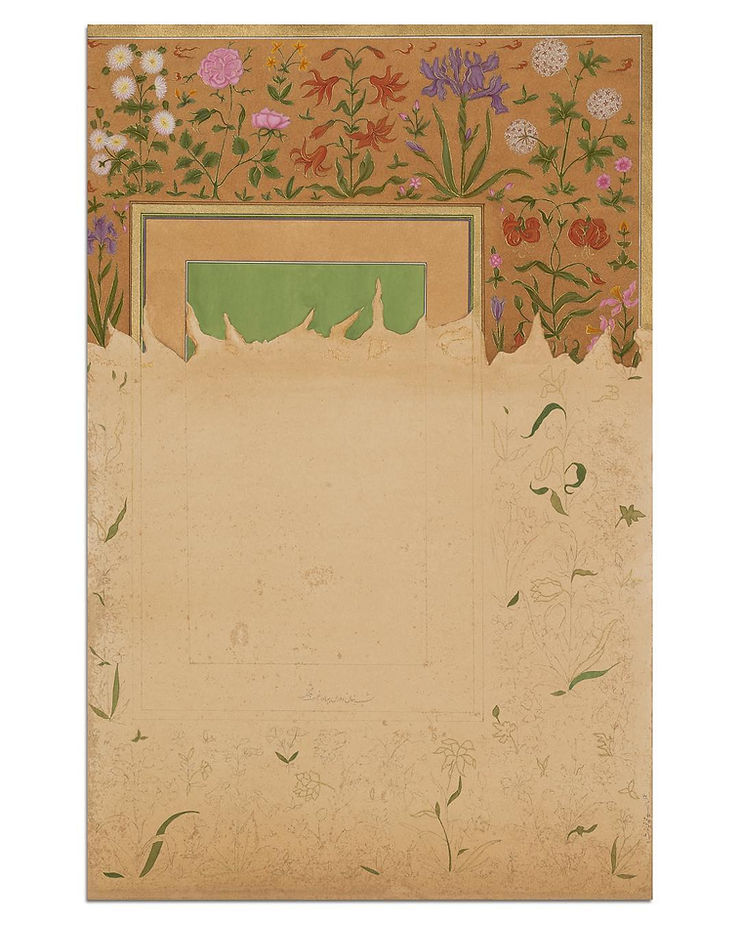

Taking his inspiration from traditional Mughal paintings, artist Syed Muhammad Khayyam Shah’s works are not only an ode to their outcome, but also to the method that leads to them. His use of natural pigments fulfills their moment in the history of art, only to present each layer that goes into their creation.

The portraits and embellishments that occupy the expanse of his canvas may often seem incomplete, but their role is to discover a likely visual evidence of what could have been the routine and activity of bygone artists. The use of colours, shapes and symbols treat human and nature alike, almost as if they shared a balanced relationship throughout.

His focus on the descriptions attached to his works comes less from a title and more from an explanation on where the subject stands in the larger history of the Mughal empire. Mughal icons continue to diversify into a contemporary mirror, with appearances, themes and stories wrapped in precious memory.

While a puzzle of differences between his paintings and specimens of Islamic art Mughal paintings would be difficult to solve, he includes multiple portraits and an asymmetrical boundary to surround his work with the past. In the moment, he unearths the beauty of intricate patterns and a devoted presence of the artist in the art.

Ya’jooj Ma’jooj

Multimedia artist Morehshin Allahyari, known for her experiential practice through multiple dimensions and a diversity in perception, chooses a story from the Qur’an to resurrect lessons from the past.

In her body of work for Ya’jooj Ma’jooj, she presents the story of two communities, belonging to Ya’jooj and Ma’jooj, who spread mischief and represent the occurrence of chaos on the planet of life. Allah, on the realisation of their deeds, allows Zulqarnain to have power to build an iron wall that would separate them from humans and detain them for their deeds. The prophecy, echoing an omen, states that some day the iron wall will crumble and their release will mark doom as it precedes ‘the end of the days’.

Allahyari draws her inspiration from the illustrations of the event that come from a rich past, merging Islamic art into contemporary notions. In particular, she chooses the illustration of “Ajā’ib al-makhlūqāt wa gharā’ib al-mawjūdāt”, meaning “Marvels of creatures and Strange things existing”, through monstrous female figures.

Her view of the characters occupies the attention of the audience and further requests them to participate in an interaction with these figures within a shrine-like place and limited movement. She utilises technology to narrate a balance between good and evil, through virtual reality. A meditative mindset leads them to discover two huge figures of Ya’jooj and Ma’jooj, as they apply certain gestures and movements, thus giving the eventual control to the storyteller who accompanies them to the 12th century, as marked in a Persian encyclopedia and visual data.

Tâqiya-Nôr

As his entry in the fifth Jameel Prize in 2016, artist Younes Rahmoun presented his journey of being captivated by Oriental philosophy and Sufism through a multimedia installation sheltering structures, patterns, geometry and numbers.

Tâqiya-Nôr, which translates to “Hat-light” portrays the discipline in Islamic thought and vibrancy through a series of domes that lie within a royal spectrum of colours. On close-looking, it may be signifying his interpretation of the Islamic architecture, demanding the same amount of engagement and observation from the artist as well as the spectator as two halves of it, which identify it as art on completion.

Rahmoun completes the image of a devoted artist, influenced by the power of culture and tradition, where he is a learner and the source of learning is his home. He relies on a calculated fate for the objects collected by him and composes the fate with multiple dimensions within a shared rhythm that emerges from working with dear ones.

While the wires that give light and accentuate the position of miniature domes run across the space to a single source of energy, their common ground certainly defines Islamic art and architecture as a call of unity, integrity and bright spirits on the sphere of the world.

It was in the spirit of grandeur that Islamic artists kept visiting events of eventual importance and framing them in the practices of painting, calligraphy, architecture, textiles, illustration when each of these practices made subtle appearances in the others. Islamic art was, and therefore will remain, a blend of royalty in every form.

While you’re at it, find a glimpse of Islamic art in the history of Indian art and its social roots here!