Bright colours, bold clean brushstrokes, and the use of inexpensive paper all are indicative of one art form – Kalighat Paintings. As the name suggests these paintings were made on the ghat (bank) near the Kali Temple in south Calcutta in nineteenth-century Bengal. Initially meant as souvenirs or mementos for travellers, it moved beyond being limited to a commodity for tourists and entered the domain of art. The Kalighat paintings portray a variety of subjects, ranging from mythology and religion to satirical depictions of Calcutta society.

The Kalighat paintings emerged in the mid-nineteenth century in Bengal. The traditional painters known as ‘patuas’ initially produced scroll paintings and would sustain themselves by going from village to village, narrating and singing the stories. They then flocked to Calcutta, settled down, and started making single-framed paintings against the linear paintings of the scrolls, with cheap mill-made paper and watercolours. These paintings were mass-produced for large audiences, especially to serve as either postcards or mementos for travellers catering to the growing tourism within the thriving industrial harbour city. Many of these paintings/souvenirs were collected by foreign travellers and were sent back home as exotic mementos from the orient.

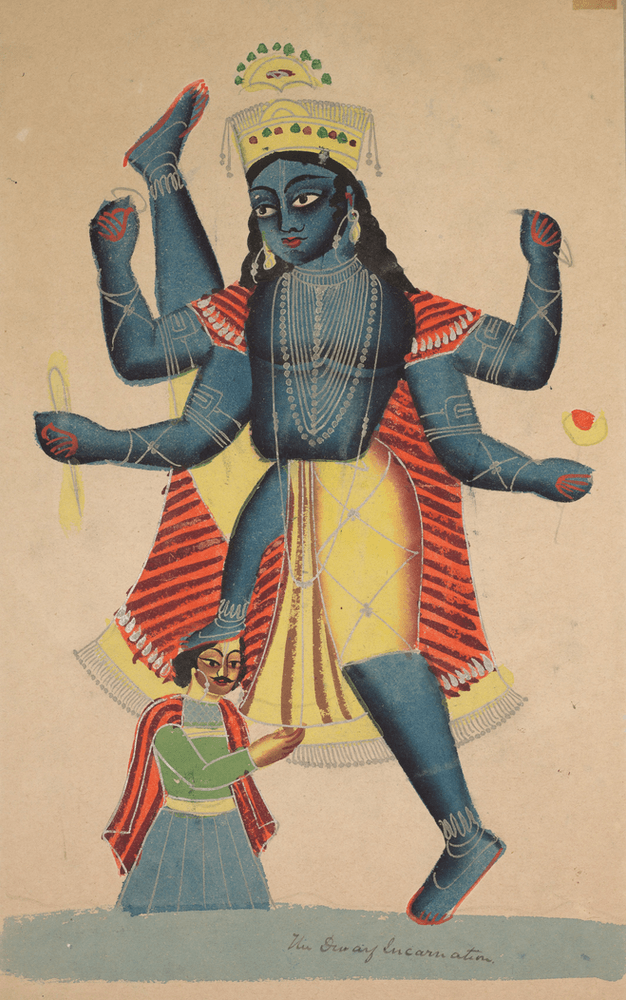

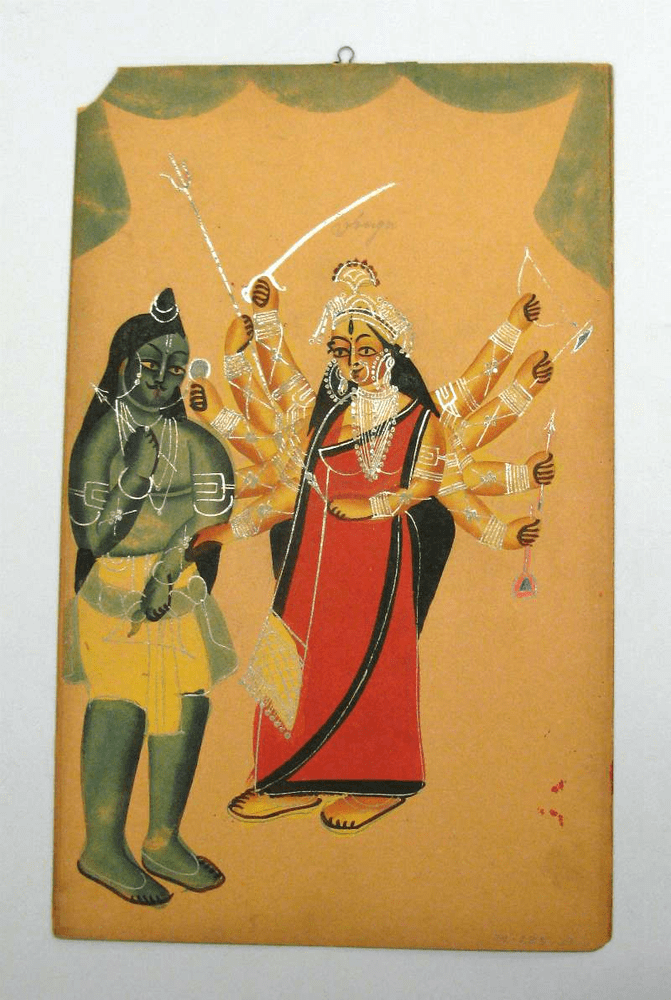

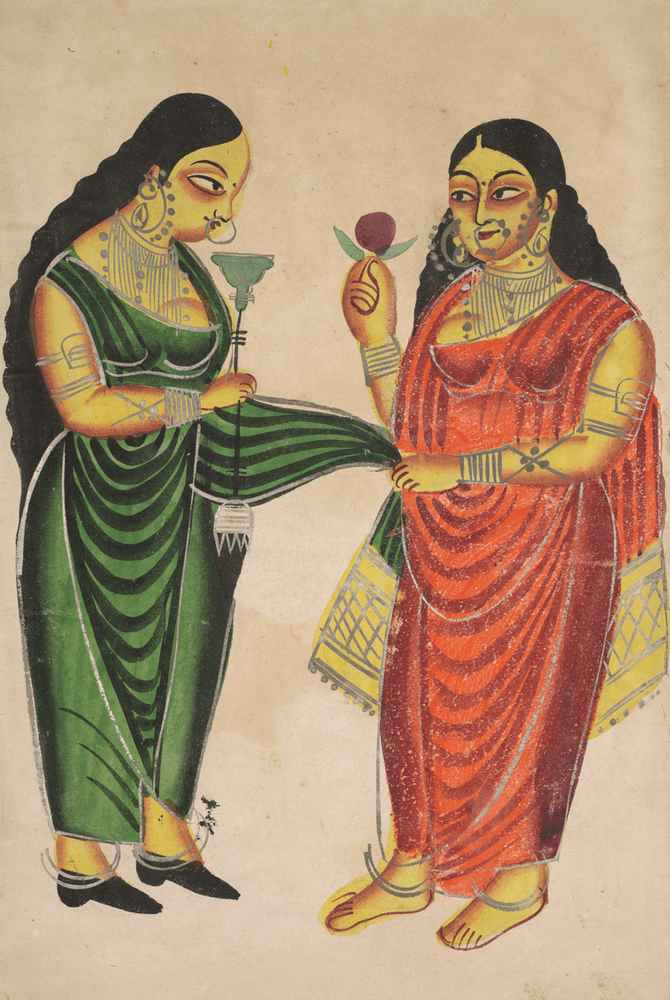

The early Kalighat paintings explored mythological and religious subjects. However, non-religious, secular, and everyday scenes were themes equally depicted. With growing urbanisation, the themes portrayed by the Kalighat paintings got diversified and began to incorporate the contemporary socio-political aspects of British-ruled Bengal.

Women in the Kalighat painting have been depicted as strong characters against the gentle, docile, nurturer iconography used for them in other Indian traditional representations. This is because the art originated near the temple dedicated to the goddess Kali.

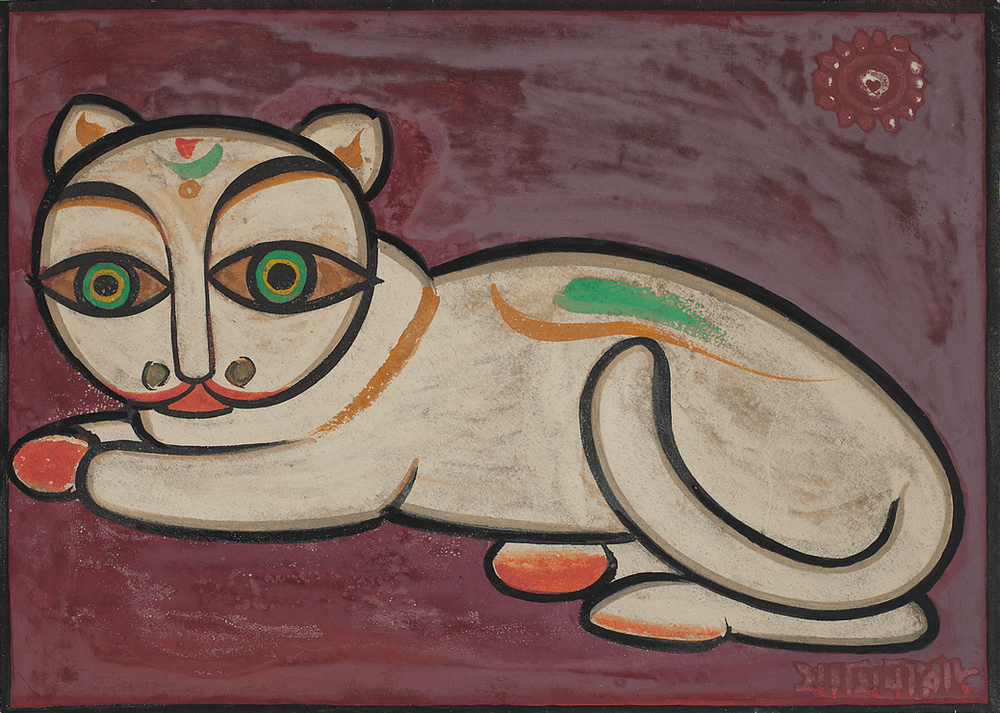

One of the major exposures of this art form came when the modern master Jamini Roy (1887 – 1972) adopted the style of Kalighat paintings. The simplicity and deep-rootedness in the Indian tradition of this art form appealed to Roy. His shift to Kalighat paintings also signified a change in the balance of power from western styles to indigenous art. Jamini Roy became a household name with his use of the Kalighat style.

Another painter who gave a fresh look to the Kalighat style in contemporary times is Kalam Patua. Kalam Patua was born into a family of traditional scroll makers in rural West Bengal. He has used the formula of Kalighat paintings in a new light painting current issues which are interspersed with autobiographical elements. Kalam by profession worked as a postmaster in rural West Bengal and therefore a few of his series depict the Indian post office as a theme.

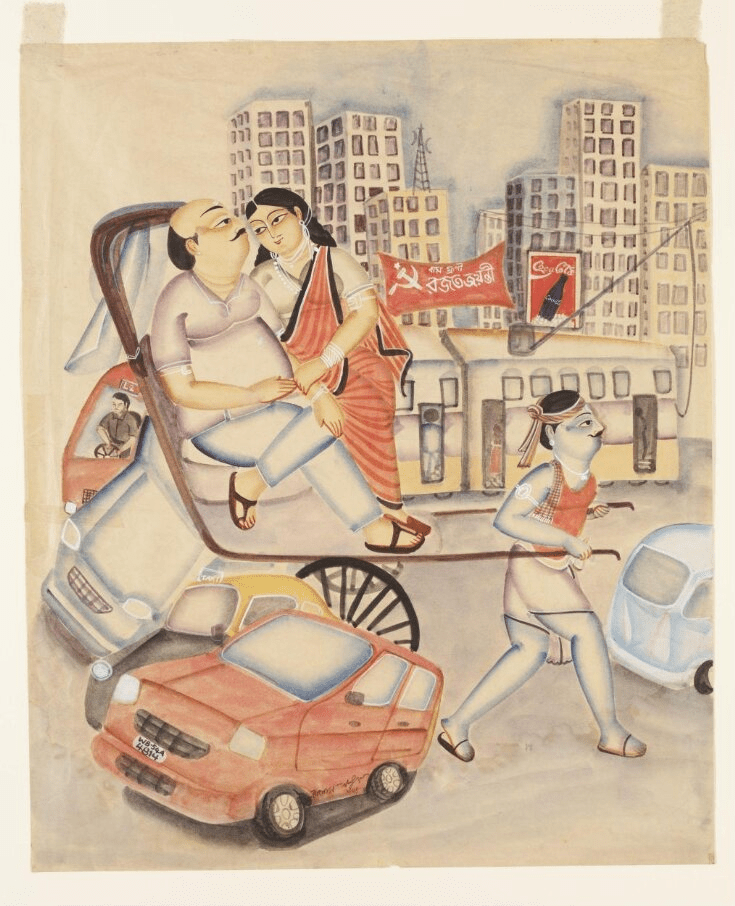

The painting is set in an urban landscape and gives a glimpse into modern-day Kolkata dotted with traffic, skyscrapers, and the fast-paced city life juxtaposed against a rickshaw puller navigating through the busy lane, carrying the passengers. The artist keeping in mind the ethos of the city of joy has depicted a tram, a car, a public taxi, and a rickshaw.

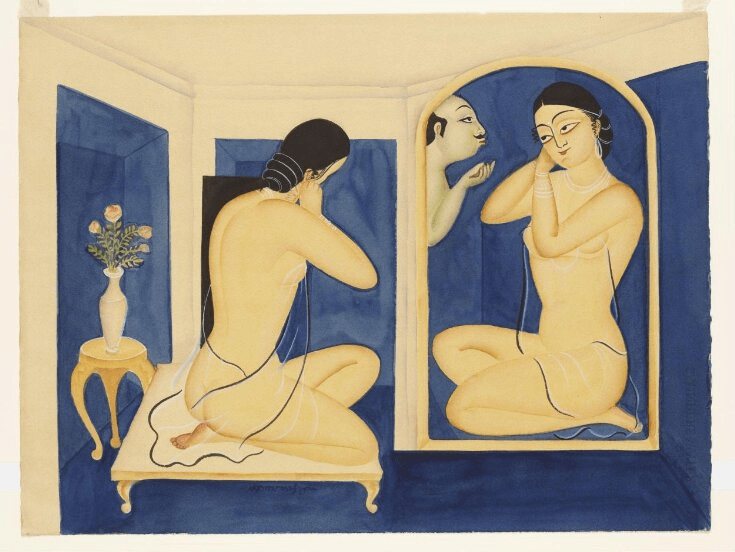

The painting depicts a lady looking at herself in the mirror and imagining her lover. The brilliant blue backdrop highlights the woman’s posture and the sensuality of the transparent garment.

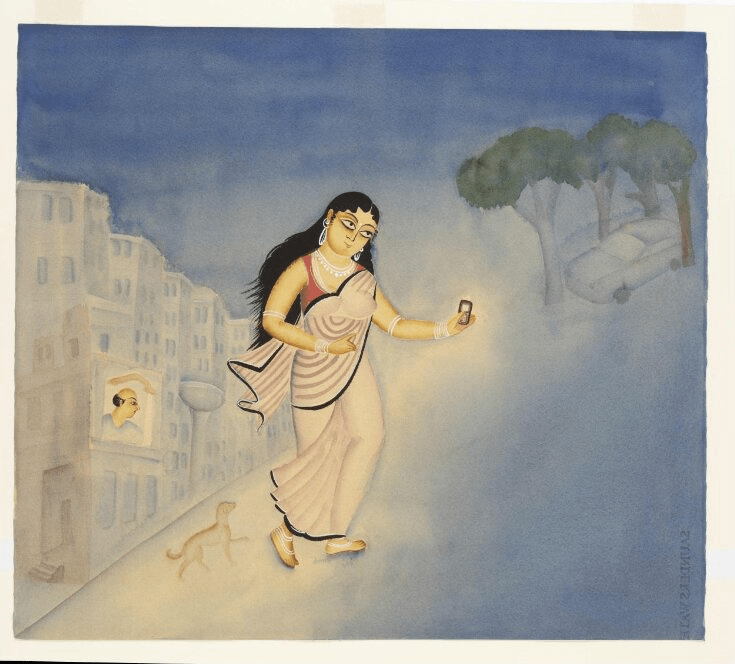

Exploring the theme of rendezvous between lovers, the painting is titled Abhisarika which translates to ‘fearless’ and is used for the heroine who has taken a risk at night to meet her lover. The age-old theme is given a modern element through the mobile phone indicating the opportunities provided by technology.

Kalam Patua is one of the very few artists who practices the art form today. The art form gradually declined after the advent of photography and lithographs. Today, it is still kept alive in the rural areas of West Bengal, particularly in Medinipur and Birbhum, however, it has died in the urban areas where it originated. These painters continue to use the traditional methods used by the nineteenth century ‘patuas’.

Please let us know in the comments below if you happen to possess a Kalighat painting or if you can spot one around you.