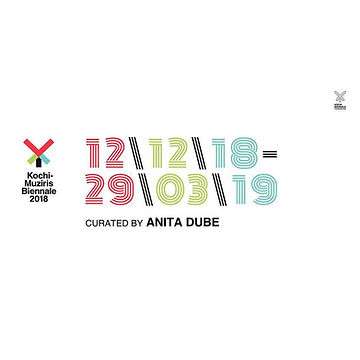

Kochi Muziris Biennale, which is now in its 4th edition, is one of the biggest contemporary art exhibitions in Asia. The biennale starts on December 12th and continues till March 29th, every even year, hosting a wide variety of art programmes and showcasing work by artists from India and all over the world over the course of these months. It was founded on the principle that art is essential in society and is a result of a conscious effort to strengthen contemporary art infrastructure and broaden public access to art across India by the Kochi Biennale Foundation.

The first Kochi Muziris Biennale began on December 12, 2012. India’s first ever biennale of international contemporary art, it has a story unique to India’s current reality- its political, social and artistic landscape. In May 2010, when the Kerala State government approached Mumbai based contemporary artists, Bose Krishnamachari and Riyas Komu to start an international art project in the state, the artists acknowledged the lack of an international platform for contemporary art in India and hence, proposed the idea of a Biennale in Kochi on the lines of the Venice Biennale. The challenge of hosting a biennale at India was proportionate to the ambition of the project. A biennale had never gotten past the conceptual stage in India before as there was no existing infrastructure necessary for an exhibition of its scale- no spaces and no institutional support structures.

Kochi is the confluence of heterogeneity, a city where more than 30 non-Malayali communities have, over the centuries, come to find refuge, trade, spiritual invigoration and much else, only to develop roots and integrate into the local society. Krishnamachari believed that it is to this shore that one would bring in the practice of contrasting adverse imagery with constructive imagery to create specificity and conviction that is often lacking in the more wishful and positive imagery, and hence, Kochi became the chosen destination for the biennale.

Biennales are deeply tied to their physical locations. The Kochi-Muziris Biennale seeks to invoke the latent cosmopolitan spirit of the modern metropolis of Kochi and its mythical past, Muziris, and create a platform that will introduce contemporary international visual art theory and practice to India, showcase and debate new Indian and international aesthetics and art experiences, and enable a dialogue among artists, curators and the public. Kochi is among the few cities in India where pre-colonial traditions of cultural pluralism continue to flourish and its traditions pre-date the post-Enlightenment ideas of globalization and multiculturalism. They can be traced back to Muziris, the ancient city that was buried under layers of mud and mythology after a massive flood in the 14th century. It is this combined flavor of mysticism and modernism associated to Kochi and Muziris that the biennale aimed to preserve, exhibit and expand upon.

Biennales such as the Kochi-Muziris Biennale belong to the fourth wave (2000s) of the biennale formation since Venice started in 1895. Critics have argued that South Asian biennales that came up in the third wave, have failed to establish their own intellectual and critical identity, that they ape the Western enlightenment projects rather than rely on their own intellectual structures and sources. By implication, they are mimetic, which asks the questions: Is there anything particularly Asian in the biennales of Asia, such as the Busan or Gwangju biennales, with their range of international curators? How does Kochi-Muziris assert its own difference?

Kochi-Muziris is, by definition, a South Asian and Asian biennale. Two things make the KMB of paramount importance in the context of the South Asian art scene and biennales that came up in the fourth wave. First, the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, located in the southern peninsula, is as much an assertion of the south-north dialectic within India as it is a significant presence in the biennale dialectic between the global south and global north. Second, it is also the first assertion of trans-nationalism from a region that has also challenged the hitherto entrenched authority of the center (New Delhi) in negotiating its regional-national and regional-global identity.

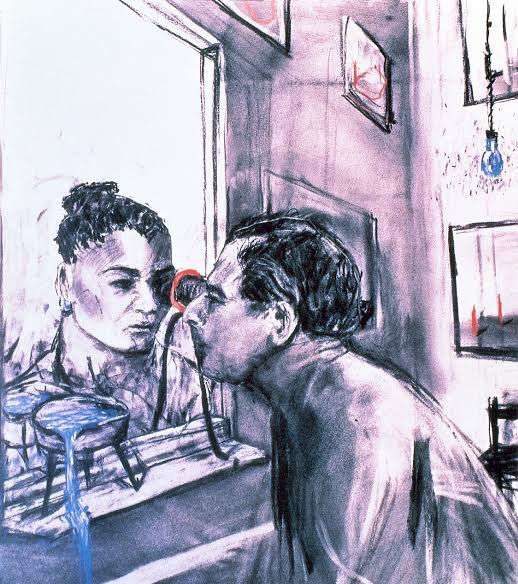

Under Anita Dube, this year’s curator, who is known for her politically charged works, the KMB 2018 will focus on the theme “Possibilities for a Non-Alienated Life”. Her oeuvre features both knowledgeable consideration and skillful melding of the sensibilities and styles of abstractions with real, contemporary concerns. A board member at KHOJ, an international artists’ association she co-founded in 1997 in New Delhi, she says in her curatorial note,

“At the heart of my curatorial adventure lies a desire for liberation and comradeship (away from the master and slave model) where the possibilities for a non-alienated life could spill into a ‘politics of friendship’. Where pleasure and pedagogy could sit together and share a drink, and where we could dance and sing and celebrate a dream together”

Her selection not only reinforces the biennale’s commitment to having artists at the forefront, but also their mission to address contemporary socio-political-cultural concerns. She is a strong proponent of making art accessible to the public through effective political and social engagement, which is what the biennale tries to do. She feels that with Kochi’s history of profitable trade, home reign and colonialism, Kochi-Muziris may be required to be a new amalgam of its cosmopolitan past, its regional present, and

its left-leaning political orientation in a period of global capitalism, which she integrates in the theme of this year:

“Imagine those pushed to the margins of dominant narratives speaking: not as victims, but as futurisms’ cunning and sentient sentinels. And before speaking, listening to the stone and the flowers; to older women and wise men; to the queer community; to critical voices in the mainstream; to the whispers and warnings of nature.

If we desire a better life on this earth — our unique and beautiful planet — we must in all humility start to reject an existence in the service of capital. Possibilities for a Non-Alienated Life asks and searches for questions in the hope of dialogue.” (Anita Dube, 2018)

The biennale takes place over a range of 10 venues which are all heritage properties that have been preserved, repurposed and developed for the exhibition. This year’s project has taken Anita Dube to over 25 countries in the search of world-renowned artists over the course of two years and the final list of artists features 93 artists and projects from India and all over the world, ranging various mediums and techniques.

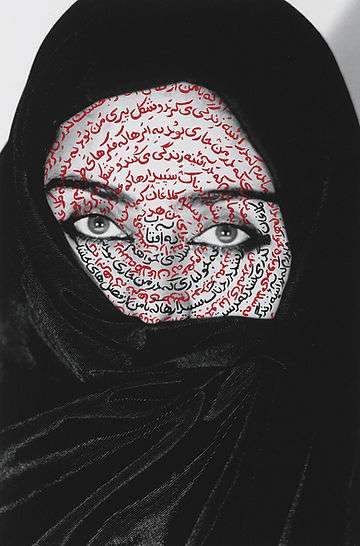

Artists in media art include Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook (Thailand), Jun Nguyen-Hatsushiba (Vietnam) and Shirin Neshat (Iran), in installation and performance art, Shilpa Gupta (India) and Tania Bruguera (China) and in animation, drawing and sculpture, we are looking forward to William Kentridge (South Africa) whose personal experience of the 20th century’s most contentious struggles, like the apartheid bring a whole new dimension to his work.

In its first three editions, Kochi-Muziris has addressed some of the masculinist positions of the past-seafaring, conquest, trade and barter, as well as the establishment of global markets. Their principal address was directed to mapping and diaspora, East and West in dialogic exchange, time and cosmology.

The fourth edition, under a female curator, Anita Dube, introduces the dimension of gender sensilbility, thereby restoring a kind of curatorial gender parity. Moreover, the fourth edition cannot afford to not highlight the shifting tides of geopolitics as in 2018, India’s concerns are very prevalent: the stress of internal migration (the second highest in the world after China), the Rohingya and Bangladeshi refugee crisis, the state of religious minorities and the eroding sense of individual liberties are all palpable concerns. The prism of gender offers a real possibility on engaging in dialogue between women across

different cultures.

Effectively, the biennale is a site of incremental knowledge as much as a claimant of cultural identity.

Sources: