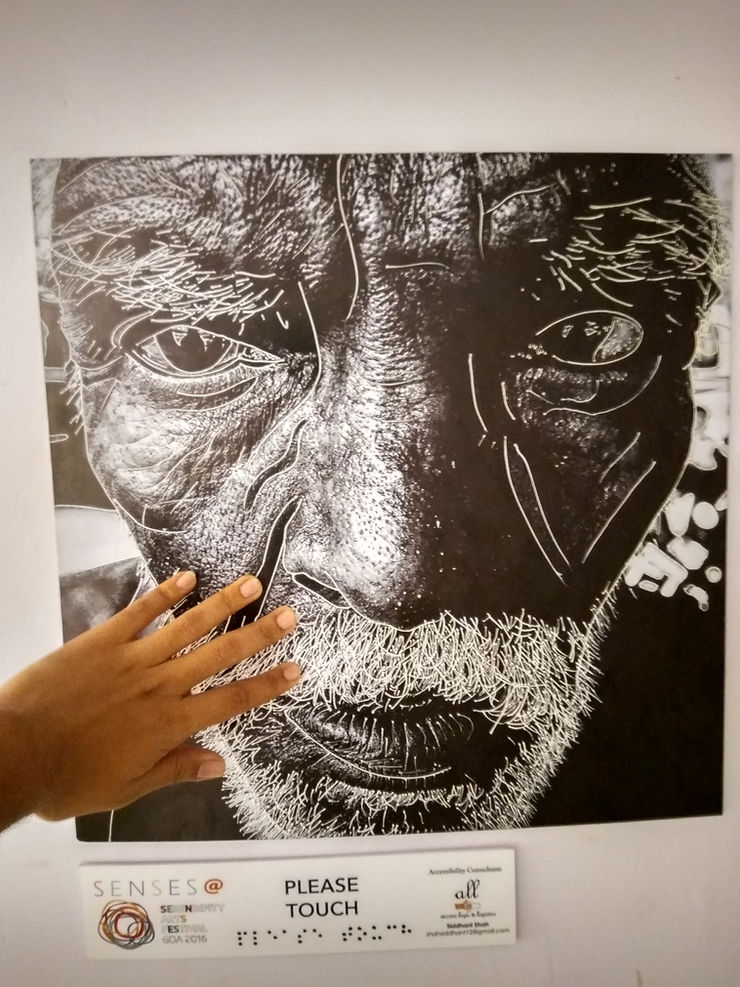

“Please Touch.” Seeing a sign board that says this— in a museum no less—one is likely to do a double-take wondering if it’s a typo. Surely the ‘not’ is missing. But the little permanent exhibition tucked away in one section of the National Museum in Delhi is clear on what it wants you to do: to not just look at the sculptures, but experience them with touch.

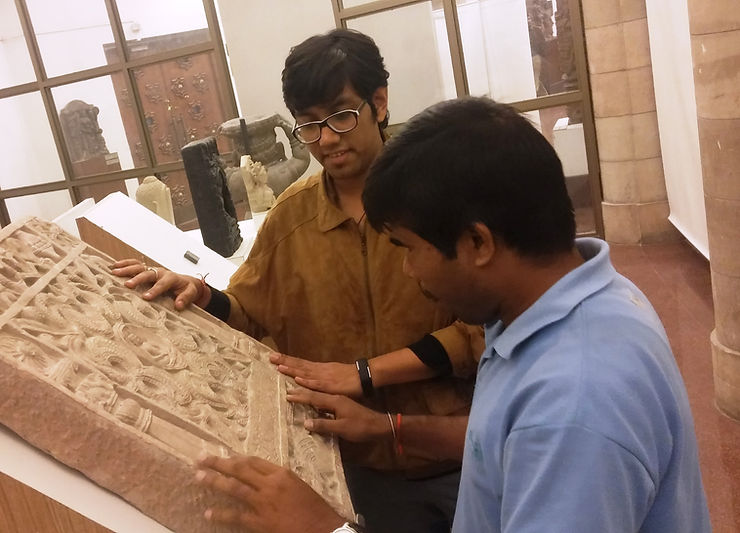

These sculptures are part of the ‘tactile exhibition’ set up by the National Museum to give the visually impaired a way to experience and enjoy the artifacts.

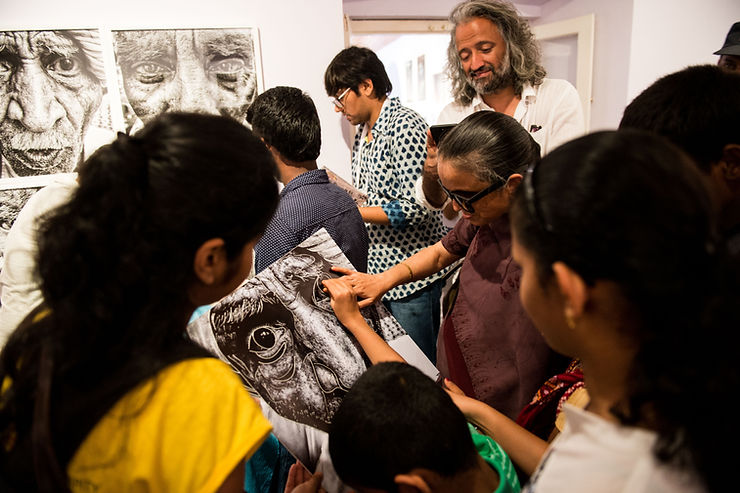

National Museum is only one of the many galleries and museums in the country that have started making special tactile exhibitions that help the visually impaired connect with the art.

Today, on the International Day of Disabled Persons, we speak with Siddhant Shah, the founder of Access for All, and the driving force behind this movement that has made art accessible to the visually impaired and people with other disabilities across the country.

What Inspired This Idea?

Siddhant was studying to be an architect when his mother developed visual impairment.

“It completely altered our lives,” he said. There were many small and big changes that took place, like going on holidays became sparse. And when they did, the experience wouldn’t be like it used to be.

“This one time, they wouldn’t let my mother enter a museum because they weren’t comfortable with having a blind person around the artifacts. She was asked to sit outside while we went in, and that really stung.” Siddhant supposes that was likely what triggered his interest in the subject, although he wouldn’t act upon it for a few more years. “It was a blow to us, but at the time, we just accepted it as it is what it is.”

In college, Siddhant and a few of his friends took part in a competition conducted by UNESCO and the Archaeological Survey of India, to make heritage sites disabled-friendly. Their entry ended up winning the competition, and in many ways, the idea that would sprout to become ‘Access for All’ was sown.

While pursuing his higher studies in heritage management at the University of Kent, Athens, Siddhant became familiar with something he had never seen in India.

“The museums and galleries there had all these provisions to make art accessible to the disabled. From ramps, to brochures in braille, to tactile exhibits they could touch. I couldn’t help but think that if my mother was here, she could have enjoyed all of this without anyone’s help.”

And that really became the cornerstone of Access for All: making art and art spaces inclusive and friendly to people with disabilities, and allowing them to access the exhibits independently.

“Tactile, Not Textile Art.”

On his return to India, with a scholarship grant in hand, Siddhant was a man on a mission. But the uphill battle had only just begun.

“Initially it was very difficult to get people to understand the need for investing in something like this at all,” he says. ‘Why would blind people come to art galleries?’ and ‘people like that don’t come here, so such arrangements would be a waste.’ are some of the arguments he’s had to reason against.

It was such a new concept in India at the time that it took some time for people to wrap their heads around it. “People would often ask us if we make textile art, and we would have to explain to them that it’s tactile, not textile”, laughs Siddhant.

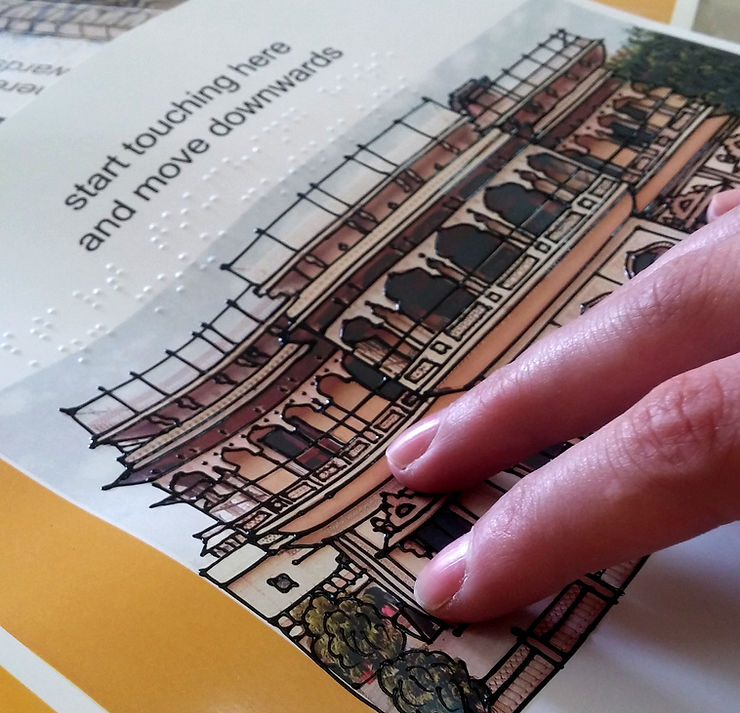

It was City Palace Jaipur that gave him his first break, allowing him to set up a tactile exhibition in their gallery premises. For this exhibition, they made their first tactile replicas of artwork, as well as the first brochures in braille. They even trained the museum staff. This was followed by a similar exhibition in the National Museum, Delhi.

“Because it was such a new idea, we needed to prove to the spaces that something like this could work. It helped that I had the scholarship money because that allowed me to set up these initial exhibitions for free. Once they saw how well they worked, the spaces were more receptive.” – Siddhant Shah

For years Siddhant and his little team traveled from city to city, state to state, trying to pitch their idea to museums and galleries across the country.

Building From Scratch With Nothing to Go By

The Delhi Art Gallery, says Siddhant, has been massively instrumental in bolstering Access for All and bringing their vision to fruition. For three years he worked with them, creating the workshop ‘Abhas’ in which they recreated the art of Santiniketan including two untitled works by Rabindranath Tagore, the painting of a musician by Nandalal Bose, a painting by Ramkinker Baij, as well as Benode Behari Mukherjee’s collages and lithographs.

Convincing the art galleries and museums of the importance of having exhibitions catering to the visually impaired was only half the battle won. Siddhant recollects the various trials and errors, the challenges, and obstacles they had to overcome to create these exhibitions.

“When we started out, there was no reference for us to go by, no textbook we could follow. We had to wing it from the start,” says Siddhant, “back then, the most obvious choice for recreating the artwork was 3D printing. But we didn’t have the funding to get even one model printed, so we had to get creative.”

For the guidebooks they created, Access for All used audio descriptions, large font texts using polymer ink, and even Mehandi to create embossed outlines of the monuments.

Another major challenge they hadn’t expected was how difficult it would be to make the braille guidebooks. “That’s when we realized, we wouldn’t be able to do all of it just by ourselves,” said Siddhant. “Braille schools refused to print the guidebooks and catalogues because they only print a certain list of academic books and they’re all quite set in their ways. The idea of printing non-academic braille books was something they found preposterous.”

“Why Do All Artists Make Paintings of the Same Size?”

“You know, I always say this, but people with sight, we often look at things without actually seeing them. This became true even when we were creating these tactile exhibits. There were things, details that didn’t strike us at first. ” explains Siddhant. “ For instance, at one of the shows, this little girl came up to me and asked, ‘bhaiya, why do all artists make paintings of the same size?’ This really struck me because at that point we were making all replicas in the size 10 by 10 inches. Her question got me to consider making each piece as close to their original proportions and form and possible.”

Apart from his mother herself, Siddhant consults other visually impaired people to proofread the guides and test the exhibits to make sure they’re as effective as possible.

How Do They Hope to Keep Things ‘Tactile’ in the New Normal?

“The pandemic,” Siddhant admits, “has been tough. But I believe a lot of the challenges are in our imagination. In March we were very apprehensive with everything coming to a sudden standstill. We weren’t sure how we would carry on, because our work majorly focused on making art accessible through touch and feel.”

However, Siddhant and his team have been busy as ever. “It really forced us to branch out and find ways to work around the problem. We have been doing online art workshops, DIYs for parents of disabled kids, and doing various engaging activities with autistic kids.”

Ask him if he’s worried about the future of tactile exhibitions with the art world taking to the digital space in such a big way, and he’s quick to say, no. “It may be paused for now, as is everything else, but the museums and the on-ground exhibitions aren’t going anywhere. We’ve just found other ways to expand our project and make it more inclusive in the meantime.”

Accessible art is not merely about enabling disabled people to experience art, but also to create art of their own. Read here about how the Serendipity arts festival celebrates inclusion in creating art.