The Saree Fences of Sindhudurga: Indrajit Khambe’s Grassroots Gaze

01 | 12 | 25

Written by Nidhi Krishna

Image courtesy: Indrajit Khambe

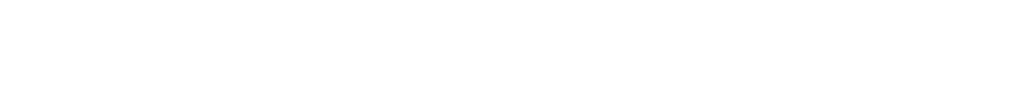

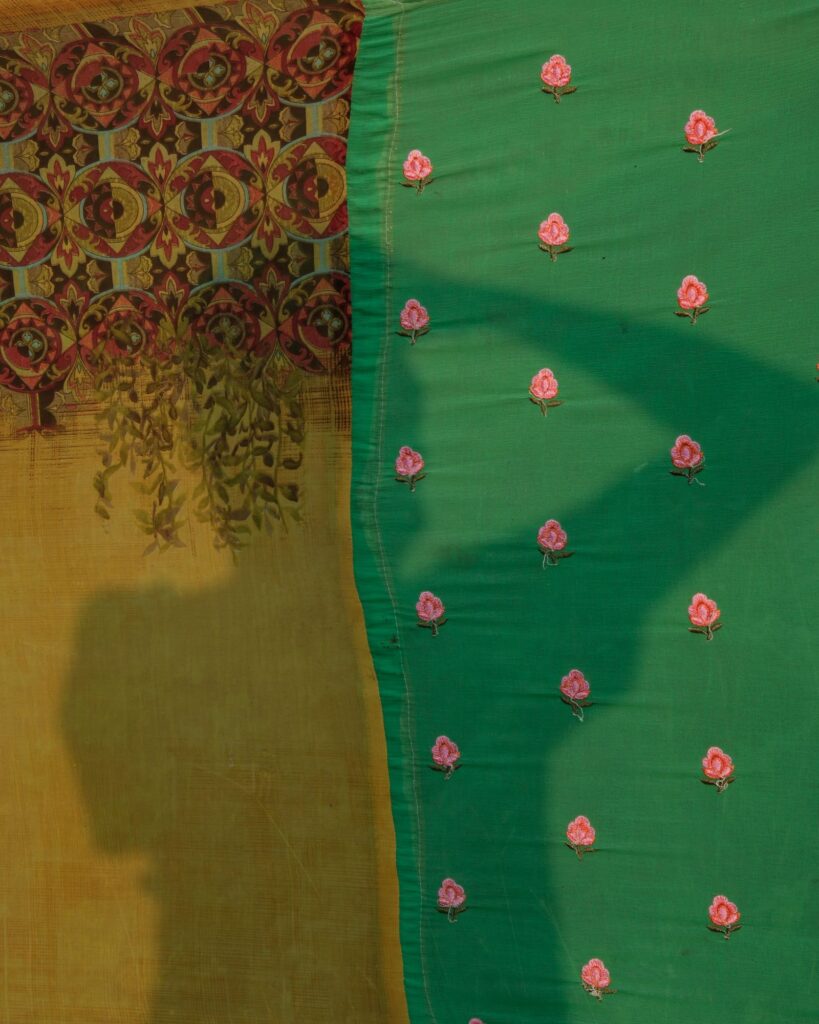

Soft sarees framed against vivid, green grass. Documentary photographer Indrajit Khambe’s images are so evocative, you feel like you could run your fingers over the fabric through the screen.

Khambe’s images of a unique agricultural practice in Maharashtra went viral on social media — drawing attention to how Konkan farmers build ‘saree’ fences to safeguard their crops from harsh weather. Their unique tradition of repurposing brightly-coloured sarees was captured by Khambe on his iPhone, garnering curiosity, awe and delight across the internet.

Khambe’s practice is rooted in his native village — Sindhudurga. His tender portraits capture the quiet, everyday rituals of life in rural Maharashtra, as well as its lush, natural beauty. His works have been featured at Zapurza Museum of Art and Culture, Stadtische Galerie in Germany, festivals like Indian Photography Festival and Serendipity Arts Festival, as well as in commissioned work for companies like Apple.

For World Saree Day, Art Fervour sat down with the documentary photographer to learn more about the fascinating saree fences, Khambe’s journey as a photographer, and why he’s interested in documenting only three places in the world—all located in India.

On Stumbling into Documentary Photography

Image courtesy: Indrajit Khambe

Coming from a family of farmers, Khambe had always enjoyed growing up around agriculture. His aesthetic preoccupations with the land and its creatures found a creative outlet in painting, but when it came to choosing a career, the arts were not a viable option at the time. After college, Khambe began a computer sales and repair business in his hometown. But the creative bug never left him. He speaks of a decade-long affair with theatre:

“After doing theatre for almost 10 years, I began to sense that it wasn’t my cup of tea. I was born and brought up in Sindhudurga, but the plays we worked with were written about cities like Pune and Mumbai. Those stories weren’t relevant to me. The sensibilities and relationships of the characters from bigger cities were not relatable to me. I wanted to talk about my stories, people and surroundings. I wanted to find a different medium.”

His initial experimentation with digital cameras began in the early 2000s. As his passion for the medium grew, he began to study the practices of photographers from around the world through the internet, which led him to develop his own creative voice.

“Photography is liberating and flexible. I don’t need anyone else — I can just pick up my camera and take off on my own. I can take photos of the things that matter to me.”

Saree Fences and Sindhudurga

Image courtesy: Indrajit Khambe

Khambe’s relationship with Sindhudurga comes through in his work. The saree fences had always been a familiar part of his surroundings, but on one particular evening, he noticed how stunning they appeared in the twilight. He turned to a farmer working in the fields nearby:

“Why do you use sarees?”

Khambe details his conversation with the farmer – “Bison numbers had been increasing in Sindhudurga over the last few years. The vibrant colours of the sarees helped to keep cattle, bison and wild pigs away from the crops!”

In an era where buzzwords like ‘eco-conscious’ are thrown around carelessly, the farmers of Sindhudurga are creating the blueprint for truly sustainable and cost-efficient practices. Upon asking the farmers how they managed to amass so many sarees, Khambe learned:

“They borrow sarees from families in the neighbourhood, or their own families. They collect old sarees from their mothers, sisters, wives and neighbours. The emotional connection that community brings; it really hit me then. That’s why I started documenting the saree fences.”

#ShotOniPhone

‘Origin of Colours’ by Indrajit Khambe for Apple. Shot on iPhone. Courtesy: Indrajit Khambe

Some of Khambe’s best work has been shot with an iPhone. He uses simple phone photography to capture various subjects, places, and communities with remarkable artistry.

“Cameras aren’t as spontaneous; you have to set them up, adjust the lighting and exposure, and the window to grab the moment might pass. But when you have a phone in your hand, you can instantly take a picture.”

In January 2019, Apple themselves reached out to Khambe, expressing their interest in commissioning him and highlighting his prowess with phone photography.

“I always thought I’d have to live in a big city like Pune or Mumbai to get proper assignments. But after the Apple project, my perspective began to change. I could continue to stay in my village and work on interesting assignments. I realised that documentary photography could be my full-time career.”

People, Places, Photos

‘Hampi – Land beyond Landscape’ by Indrajit Khambe. Courtesy: Indrajit Khambe

“Many photographers like to explore new locations for new projects. But whenever you visit a new location, you feel overwhelmed by unfamiliarity. You find everything interesting, and want to capture everything without actually pausing to observe the details. There’s a pressure to perform. But in my own village, I see the same places everyday, and travel the same roads everyday. I don’t need to perform. I’m able to actually observe minute details.”

Khambe firmly believes that, “a photographer’s relationship to a place should be like the one they share with their best friend.” There are only three locations he’s currently interested in documenting for his own body of work: Sindhudurga, Hampi, and a small fishing village near Dapoli known as Harnai. He likes how accessible those locations are — places he can reach with just a car. He repeatedly visits these sites, documenting stories, faces, landscapes — unravelling each new detail with the ease of someone who truly refuses to race against time.

In a world where ‘productivity-maxxing’ and ‘make every second count’ are phrases in annoyingly frequent circulation, Khambe’s practice is a reminder to slow down and reflect on the present. He advocates a gaze that is not externally imposed and distant, but inwardly focussed and intimate.

“I want to understand myself through my work. When I spend so much time in nature and the quiet, I am able to understand myself better. It might sound romantic for a few days, but when you do it for years on end, you are really forced to look deep inside yourself; to become comfortable with solitude and being with your own thoughts.”

Western photographers have often documented the subcontinent through an ‘Oriental’ lens’; one need only remember the ‘Afghan Girl’ to understand how a privileged West reduces billions of diverse peoples and places to a singular, problematic gaze. But it’s not just Western photographers who fall into this trap; plenty of urban-educated, caste and class-privileged photographers and visual artists inadvertently repeat the cycle by bringing their own preconceived notions to the table when capturing rural life.

Through his practice, Indrajit Khambe subverts both tropes. His photography, identity and relationship to places are interwoven with his life. When we look at those dusk-dappled saree fences, we don’t just learn about a lesser-known sustainable agricultural practice, we unlearn our own biases about what ‘sustainable’ and ‘rural’ look like.

We experience the saree fences the way Khambe must have experienced them; a billowing archive of family heirlooms, a community’s memories pressed forever into soft cloth.