Pro tip – Look at Old Master paintings under natural light, not artificial. Wear shades if you can’t alter the source of light. Why? It’s simple: these were made under sun or candlelight – and depending upon how that natural light fell on the canvas, they painted their themes. Electric light bulbs would not mimic the same effect, and you might just miss out on shades that would only be visible under natural light.

This then was the predicament the middle ages had to go through. Fields of bright colors on the canvas are viewed today in the knowledge that these were made in ill-lit settings. More than six-hundred years later, however, something similar happens at a workshop in California.

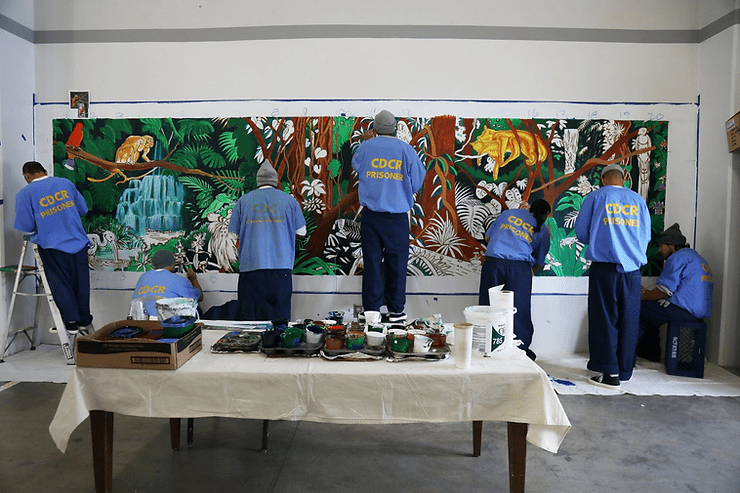

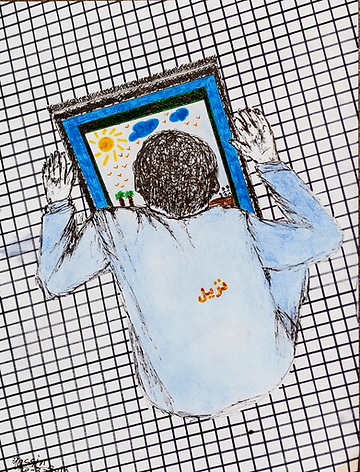

Here, groups of twenty, thirty gather twice a week for mural class. They work on a typical rainforest scene, the shades of which require an acute knowledge of playing with light and shadows. Yet for them, this is their biggest challenge since they spend most of their time living in dingy spaces, usually with no source of natural light.

That’s because this mural is made by the inmates of the Salinas Valley State Prison, where cell space normally is anything between 40 and 60 sq ft., and color and light are elements in short supply. Thankfully, sunlight fell dancing through the bars when the State of California invested $6 million in the ‘Arts in Corrections’ program. All 35 of California’s adult prisons now engaged in providing high-level offenders art – including Native American beadwork, improvisational theater, graphic novels, and songwriting.

“I don’t have much of a legacy. This is something positive that helps me focus on getting out,” remarks an inmate, who’s serving 41 years for armed robbery.

Flightless bird, American fetters

American hearts and minds have reserved a special space for Alcatraz prison – home to dangerous men like Al Capone and Machine Gun Kelly (no, not the rapper), and an evergreen feature in countless books, movies, songs – we’ve mostly been initiated to its horrific history. ‘Future IDs,’ an undertaking of the

Alcatraz Arts Project then is a much more humbling effort in bringing happiness.

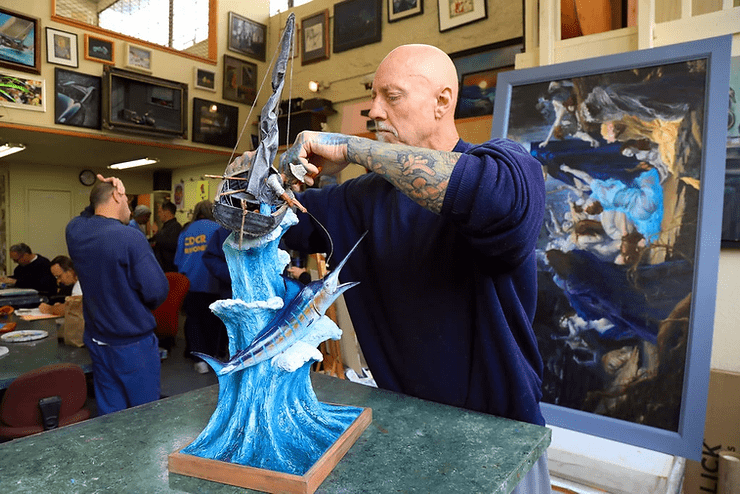

One of the most dehumanizing aspects of incarceration is the disuse of your unique name and the institution of a number. For Future IDs, new identifications were imagined by the artists – a conviction to showcase a life beyond prison for people with convictions. For Bruce Fowler – an inmate of the notorious San Quentin prison – these new IDs were rooted in hope and transformation, unlike the ‘soulless’ IDs of the prison service. Fowler imagined his new ID as that of a captain of a ship, and his love for maritime themes has found new joy with the sculptures he now makes in his studio.

Rehabilitation, with our unidimensional idea of how prisons (and prisoners) are supposed to be, has had a complex history. The kernel here has been the prison yard, where a specific image of (toxic) masculinity is projected. In such an environment, an art project breaks that image. As Laura Pecenco, a professor of sociology points out, “The criteria of being a good artist is different than being a good prisoner. Being a good artist requires vulnerability.”

An integral component today to the movement of Black Lives Matter is the institution of police, and by extension, pillars of mass incarceration. In such a light, it is a bigger imperative for the authorities to not be an institution of abuse, but rehabilitation. Prison authorities today are looking at art not from the understanding that it would not change criminal thinking, but rather change behavior within a prison. Art in this manner becomes a powerful force in driving discipline and ultimately, preparation to return to society.

Top – and locked up – Ramen

Instant noodles are an inmate’s most prized possessions, being a metaphor for gold. Ramen is not only a culinary staple but also the choice currency for barter. Ramen allowed Edward Schank, an artist-inmate of CPA’s Prison Arts Program, to express life in prison when the exhibition ‘How Art Changed the Prison: The Work of CPA’s Prison Arts Program’ opened in Connecticut.

Schank’s sculpture was a result of weaving together 1,374 packets of ramen. Food rationing in American prisons has meant inadequate food supply – and a simple ramen box is seen as valuable as a precious metal. Quite beautifully then, Schank’s work is titled ‘Self Portrait Jewelry Box.’ The exhibition also highlighted the quotidian items inmates found in their cells to make their works: ramen noodles, toilet paper, soap, tape, etc.

The Prison Arts Program, one of the oldest in the States, in its catalog explained its thought-provoking vision: “This is an exhibition of work by real people trying to do great and good things in dark worlds behind razor wire in your neighbourhood. Please do not see this exhibition as a trip to the zoo or the opening of a cabinet of curiosities. This is an exhibition of sincere attempts to confront darkness.”

Sentenced to the pencil

Such programs, however, also draw a complication.

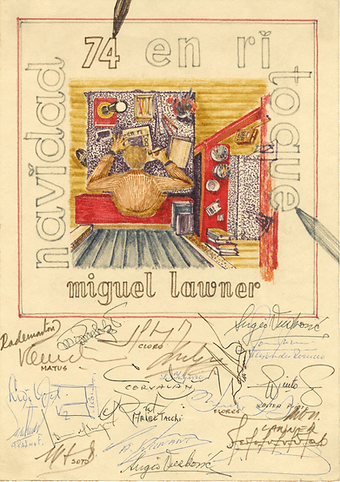

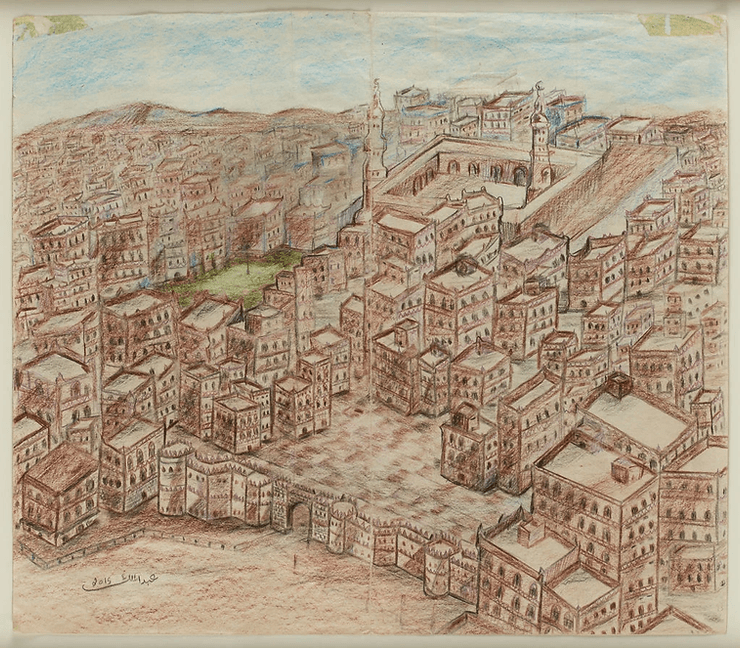

With over 140 drawings made during the French Revolution to the present day, ‘The Pencil Is a Key’ opened in SoHo last October to explore the many ways artists have used drawing to envision their freedom while incarcerated. Included in the roster were works made by imprisoned French revolutionaries, Native Americans, people forced in labor camps – and even works of celebrated artist Ruth Asawa, who was part of the mass internment of Japanese Americans during WWII.

Abdualmalik Abud’s ‘Walled City.’ Abud spent 15 years in Guantanamo Bay, drawing this cityscape from memory. Courtesy of Abdualmalik Abud/NYT.

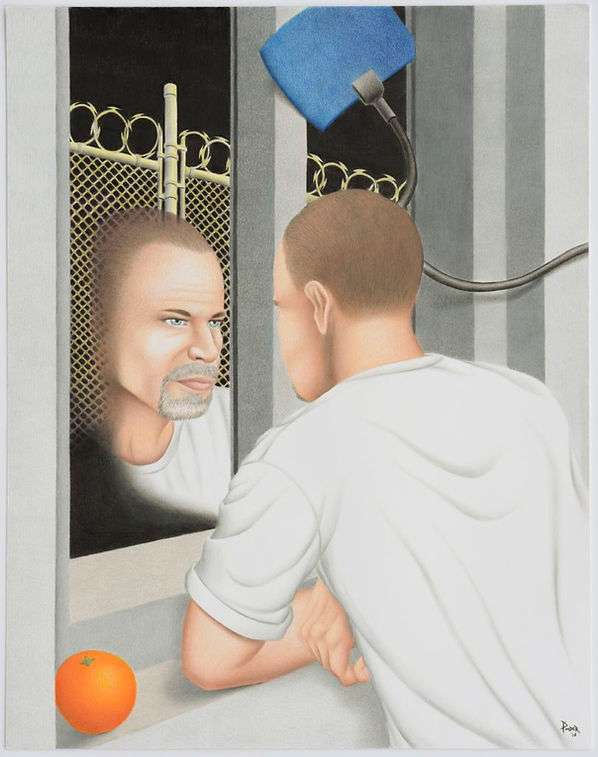

Where then is the problem, you wonder? It is with us, the (free) viewers of this art. Explaining in her latest book, Nicole Fleetwood, an art historian argued that it’s incredibly hard to change people’s negative perceptions about those who are in prison. This cuts right into the ‘separating-the-art-from-the-artist’ debate – how are our prejudices to be taken (and checked) into account when we know the history of the artist?

Colorful confinement

Royal Mughal atelier, Company School of Painting, and now Tihar School of Art. An initiative that began at the behest of the Director-General of the prison and the administrator of Lalit Kala Akademi, or the National Academy of Art, Tihar – South Asia’s largest prison – is now a hub of art.

Working on a similar idea of easing out of the trauma and stigma the incarcerated face, Tihar worked with the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA) in hosting ‘Expressions,’ an exhibition of paintings by the inmates. And apart from providing a vocation to spend the long hours away, the venture is also enriching the artists – quite literally. For example, as reported by Hindustan Times, Mohammad Ayub, an inmate, has reportedly made Rs 1.6 lakh from his paintings being sold, also making art the most sought after craft in the prison’s rehabilitation program.

.

Thane Central Jail’s inmates have also contributed to the Art from Behind Bars (AfBB) exhibition, an annual event that sees the participation of several inmate-artists from Maharashtra, an exhibition that is working towards promoting such skills and providing a sense of stability and hope to the incarcerated.

Despite the sincere effort, Fleetwood’s concerns are echoed in our subcontinent as well. Kavita Shivdasani, who envisioned the AfBB exhibition, has found patrons skeptical about buying artwork ‘made by jailbirds,’ not wishing to own works that have been made by a convict.

Such concerns have largely prevailed in almost all instances where an engagement was sought with the public about prison art. Yet as a volunteer of the AfBB puts it, “In those squalid conditions and with limited resources, if you are able to create something, that’s art.” And you’re right in wonderment to question – when inmates are overcrowded in squalid conditions, who would have the space to think about Impressionism? Yet as more and more examples turn out, seems like dingy rooms are doing quite less in suppressing such thoughts. These programs are instilling the positive belief that art can make a difference.

History isn’t far behind in providing examples of art that have emerged from areas of confinement and exclusion – take a look here at how age-old artists engaged with living in isolation.