Yes, it’s finally here. The end of this harrowing year. And we get that the last thing anyone wants to do is relive it. But if this curveball of a year has taught us anything, it is that you never know when disaster may strike, and how long said disaster will last. The year may be coming to an end but that doesn’t mean our woes necessarily end. Now before you think I’m descending into a pessimistic speech that grumpy old Schopenhauer would be proud of, let me backtrack a bit.

From world wars, to plagues, to possibly mutated viruses that have kept us indoors all year, our history books are full of the disastrous events that have befallen humanity. They are also testaments to our ability to power through them as a community, emerging—stronger, united, and humbled.

And it is this sense of community, compassion, and resilience —that especially reveals itself in times of crisis—that we’d like to look back on and celebrate.

This past year has answered for us the age-old question of, ‘What’s the point of art?’ Whether it was fine art, street art, books, movies or music, art has undeniably held our hands through the mix of anxious disorientation and boredom.

But more than anything it has shown us the power of visual art and the stories they tell.

We look back at some significant events that took place in the art world in 2020 and set the stage for the future.

Putting the Art in Activism: Patrisse Cullors

The Black Lives Matter movement, co-founded by artist Patrisse Cullors in 2013 started as a hashtag in response to the shooting of unarmed black teenager Trayvon Martin.

This year, even amidst the lockdown, the movement found momentum like never before after the killing of George Floyd, who died in May after a police officer knelt on his neck during his arrest in Minneapolis.

Art has been in the DNA of the movement from its very inception, and like many other popular movements around the world, has often fuelled its fire, making this year a big one for Cullors.

A victim of police brutality and systemic racism herself, Cullors’ powerful works have always been an expression of her political thoughts, and with the Black Lives Matter movement, she created an infrastructure for artists to use art in social activism.

This year, Cullors also designed an MFA program in social and environmental arts practice for Prescott College in Arizona, to “train new artists at the intersection of art and activism that is so critical.”

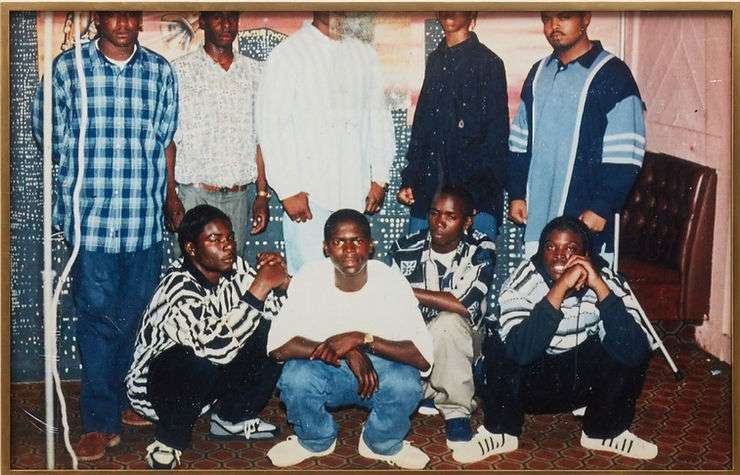

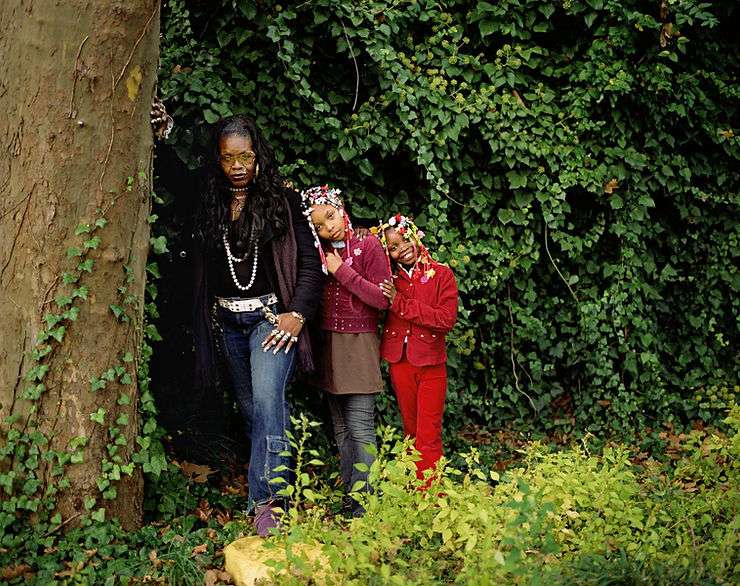

Building Homes, a Picture at a Time: Deana Lawson

While the year has shackled us indoors for the most parts, the art world saw other kinds of shackles being broken, with artists from minority communities claiming their rightful spots on the podium.

In October, African American visual artist Deana Lawson became the first photographer to win the prestigious Hugo Boss prize, for her “indelible” contributions to her medium, and to the cultural landscape more broadly.

Deana Lawson’s journey as an artistic photographer officially started in 2004 when she received an MFA from the Rhode Island School of Design. Her fascination with real people and the exceptionality that hides between the cracks of their ordinary lives have led to her creating these almost documentary-like photographs.

Lawson finds her subjects on the streets, in grocery stores, on the subway. From these strangers she constructs freeze frames of intimate scenes of domestic and familial interactions.

From backyards to bedrooms, Lawson transforms everyday spaces into striking backdrops, made crisp and theatrical. Her carefully constructed photographs that tip over into naturalistic, spontaneous moments caught on film, are defined by this fine line they walk between normalcy and drama.

Lawson’s win is not only a momentous win for photographers who use the medium for artistic expression, gaining them the kind of validation from the art world as other mediums, but also a leap forward for artists and women art practitioners, especially women of colour.

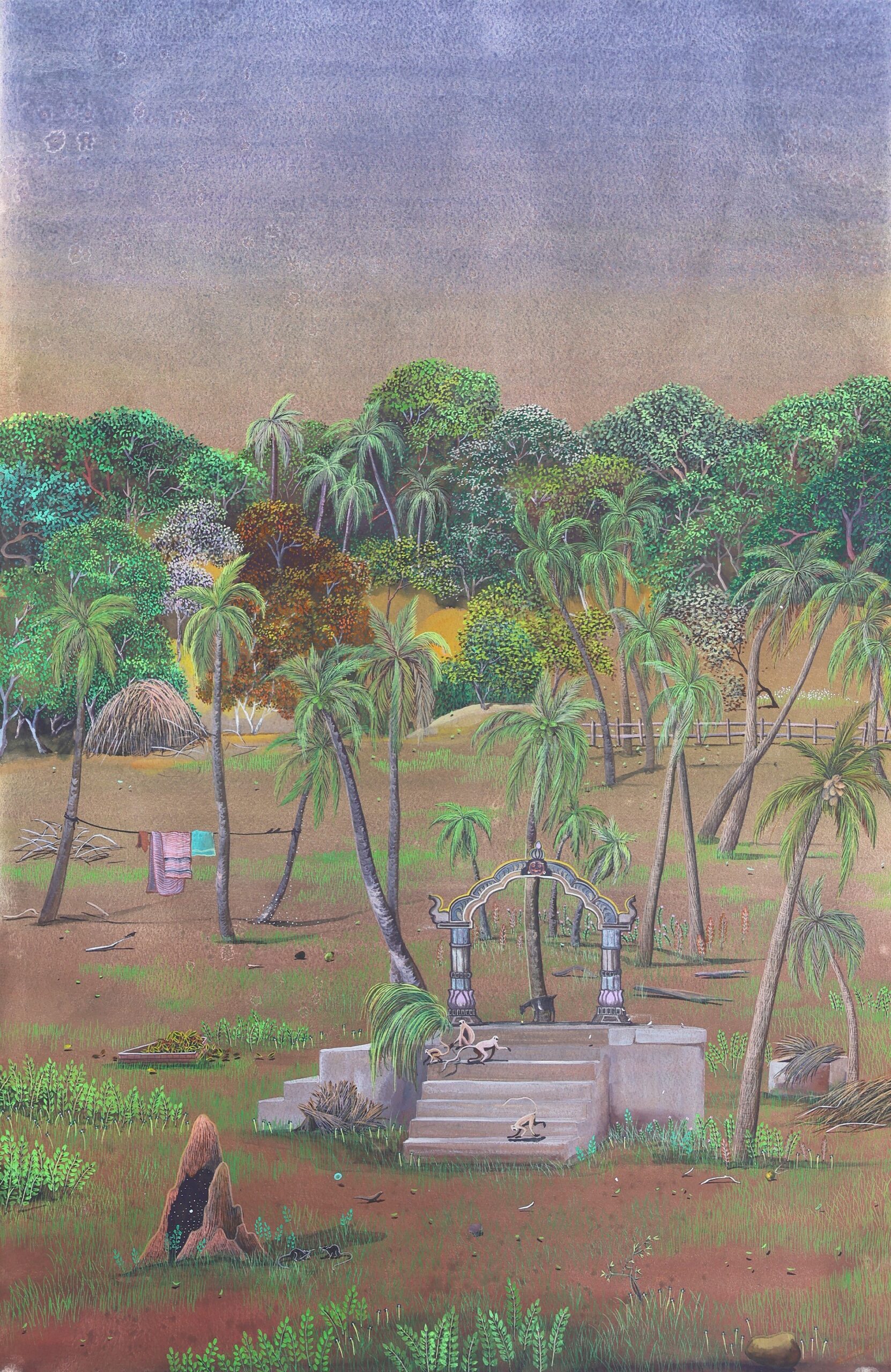

The Edges Take the Centre: Brook Andrew

A black T-shirt with the words, ‘the only primitive is Eurocentrism’, hangs from a clothes hanger. A heated metal plate, in a red room, onto which drops of water fall from above. When the droplets hit the surface they evaporate in a puff of steam, but leave a mark. These are some of the installations that you could have caught at the Biennale of Sydney.

The Biennale of Sydney this year might have seemed simplistic, yet the artworks on display exude power. The modest exhibition was intentionally created so as to cut through the Eurocentric art world’s obsession with money and fame, and bring forth the voices of artists from marginalised communities.

This exhibition got its wings thanks to Brook Andrew, a Wirajurian/ Celtic artist who made history this year by becoming the first ever Indigenous artist to be appointed to lead the Biennale of Sydney.

But, his bucket list didn’t end there. Andew’s appointment is a landmark moment considering the history of Australia’s oldest and largest Biennale. And Andrew has used his platform to turn this year into one that subverts how first nation artists and their stories are represented in the artworld.

The Biennale held between March and June was called NIRIN —‘edge’, in his mother tongue—aimed to upend the Western-centric, colonialist traditions of biennale exhibitions. The exhibition featured the works of 98 artists from 47 countries “showing how all those edges come together to make a centre”.

Andrew’s Provocative art has always been one that consciously places itself on the faultlines of the now, such as gender, sexuality and race, the environment and what art and biennales are and do, where old definitions are broken down and reformed. And with this historic appointment, he is able to open the floor to other artists from marginalised communities, possibly setting forth a rearrangement in the ‘Eurocentric art world’.

When Online Became a Lifeline

Confusion. Anxiety. Uncertainty. This is what March of 2020 looked like when everything came to a sudden standstill and we were left groping blindly in the dark. The art market, to their own surprise, gained its footing faster than expected.

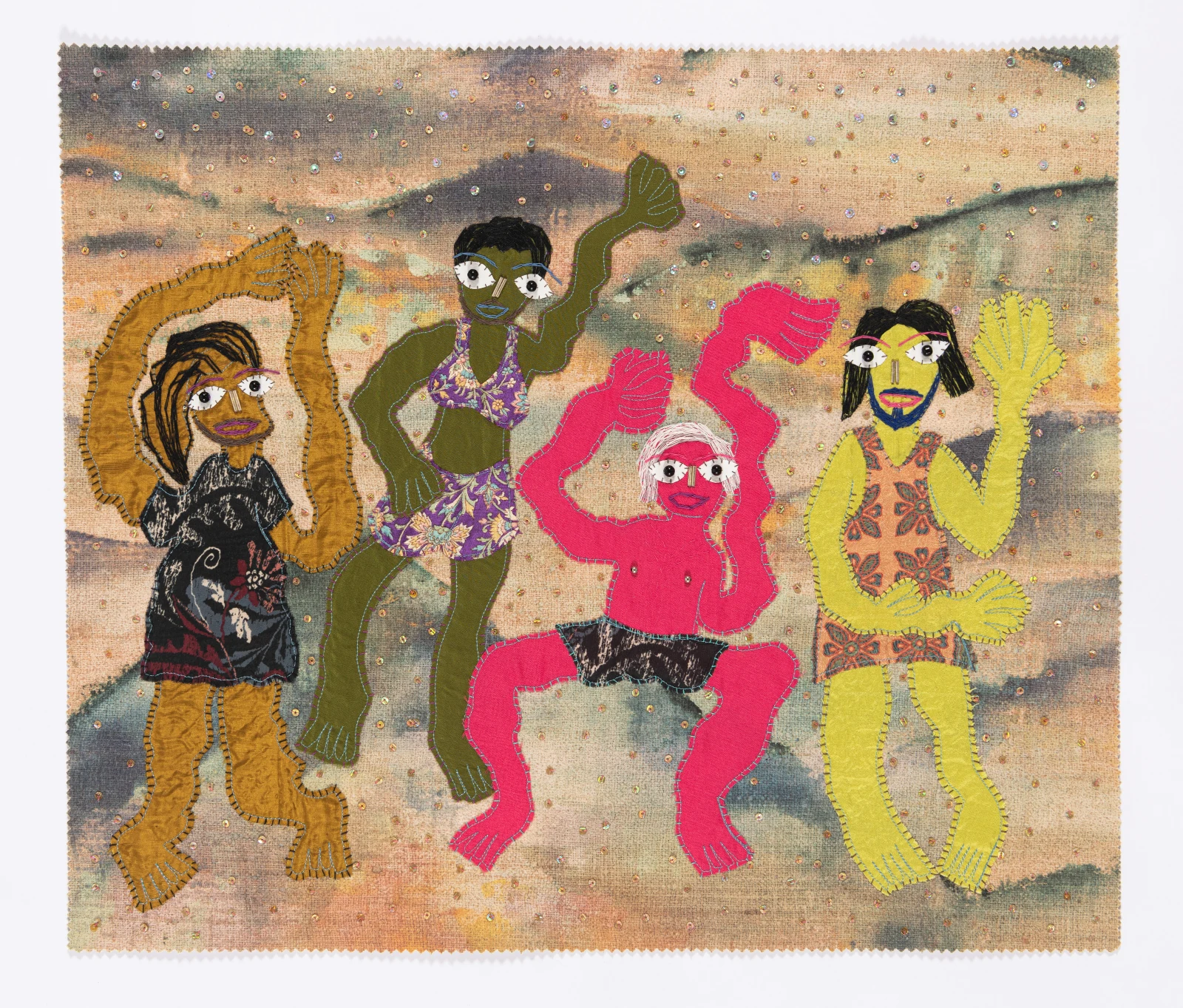

Virtual auctions have led to the art market booming in an unprecedented way, with some of the most expensive artworks in the world being sold this year. While the ease of access has led to art market favourites like Francis Bacon and V S Gaitonde breaking auction records this year, it has also created visibility for emerging contemporary artists in the scene.

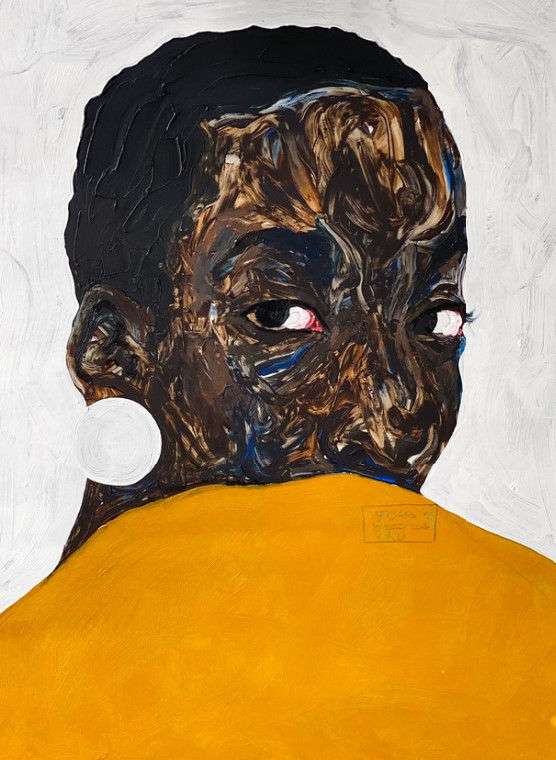

A few years earlier, Amoako Boafo was in Accra, Ghana, struggling to sell works for $100 apiece to support his mother and grandmother. In February he made his auction debut, where his The Lemon Bathing Suit sold for an astonishing £675,000—more than 13 times its high estimate, making him one of the hottest living artists of 2020.

For the rest of the year, Boafo’s works kept shattering expectations and selling for far beyond the estimated price.

Boafo is one of many emerging artists who have seen unprecedented success thanks to the buying frenzy that was set off among collectors this year thanks to virtual auctions.

Boafo’s rise to fame is also the product of an interesting shift in the art market that has been underway in the recent past. A shift away from ahistorical works of overwhelmingly white artists toward a fuller story of art.

And against the backdrop of today’s popular discourse about representation, a Ghanaian artist’s eye-friendly, vivid portraits of Black figures are only likely to increase in value.

The year has been undeniably hard for artists. But how have photographers been fairing? Read here about photographers in isolation and how they cope.