Transmedia artist Ali Akbar Mehta’s journey has been one of continuous learning and unlearning. There are several roles he performs as artist, curator and researcher to focus on alternative, innovative and inclusive discourses.

In a conversation with Art Fervour, he explores ‘archiving’ and the ways it translates as an artistic practice, poetics and performance.

How did your association with art begin? Have your experiences and the interactions you’ve had across contexts changed it in any way?

AM: ‘Art’ could be considered the overarching word to describe what I do as my ‘artistic work’. My own assumptions and understanding of ‘Art’ have changed over time and I am happy that through this interview I am offered a chance to explain and unpack what I mean by this

After ‘The Ballad of the War that Never Was, and Other Bastardized Myths’ (2011), my first solo exhibition at TAO Art Gallery, Mumbai, I had a growing sense that only painting was inadequate to fully articulate what I wanted to express through my work. Fortunately, in 2012, I had the opportunity to be at the ‘Space 118’ residency in Wadibunder and Mazgaon. Here, I decided to document Mazgaon – in part to fulfill the desire to revisit this area that I visited as a child with my grandparents.

This documentation process subsequently grew into a two-year archival project to document key architectural and oral histories, and through it the socio-political framework of Mazagaon as an area that was once the center of Bombay. This project, called SITE : STAGE : STRUCTURE, culminated as an exhibition that integrated books, objects, photographs, short films, audio narratives, and heritage walks as a way of revitalizing memories and telling a history that is absent from the formal narratives. Exhibited at Clark House, in 2014, it marks the beginning of a journey to explore particular artistic processes that only much later I connected to a larger oeuvre of “archiving as an artistic practice”.

In your opinion, what are the traits that are capable of bridging the gap between physical archives and cyber archives?

AM: ‘Cyber Archive’, a portmanteau of the words ‘Cybernetic’ and ‘archives’ is a term not previously used in the archival process. I coined this term during my MA thesis and define it as being based in the framework of Cybernetic relations – explaining it simultaneously as a technical term (concerned with archival technology); as well as a political term (concerned with the socio-political ethics of archiving).

Philosopher Achille Mbembe defines our present as “an era of interplanetary entanglement” and Giorgio Agamben claims that we live in “a state of exception”. And yet, we are also living in a time that can be defined as “archival time” – a time defined by the processes of digital archiving of ourselves, or ‘lifelogging’, where we generate trillions of terabytes worth of data as material daily. This is a unique situation that characterises our present, yet it is this that also offers a window to connect older, physical archives.

How do you explore the mid-ground between making art and writing about art to represent a particular concept?

AM: Well, it depends, firstly on the kind of art-making one is talking about. Many visual artists have asserted that for them, the relationship between words and a visual language can never be met with any sense of equanimity. They choose to keep away from any form of writing, whether explanatory or not, or prefer someone else to do it – and deem it inferior to their time and creative skill. This is the environment we have witnessed in India – one that starved critical thinking within contemporary art. But several visual artists also attempt to carry both image-making and writing as tools of making art, as well as to produce supplementary knowledge.

For me, making art and writing about it is a relationship of equal partnership in the quest to create knowledge systems. Writing about a work, or an artistic practice, whether my own or for others, is also about the ability to find different lenses through which to see the world. The shifting of an artist, to one who views it, to one who may be able to view it critically, and view it within the framework of a larger socio-political relevance, are to me steps in the transitory mid-ground that you are asking about.

What inspired you to start the Museum of Impossible Forms? Does it find a place in any of your other personal projects?

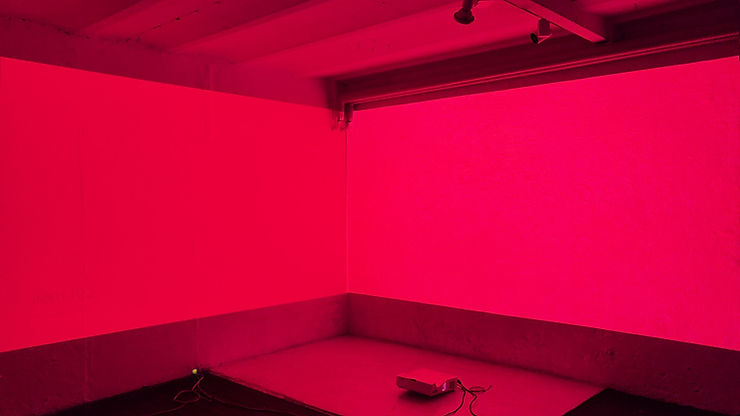

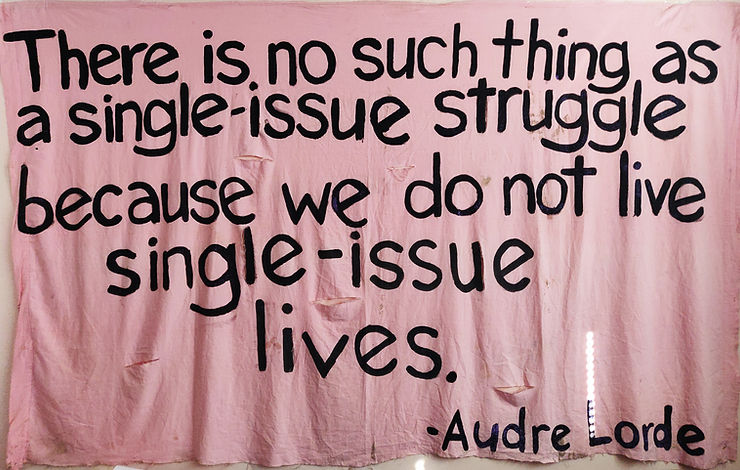

AM: Museum of Impossible Forms was founded in 2017 by a collective an independent group of Helsinki-based artists, curators, pedagogists, philosophers and facilitators, art and cultural workers, united by a common goal to fill the gaping void in the art and cultural scene regarding adequate spaces for BIPOC artists, and to counter the belief that culture is only found in the center. Over the four years, m{if} has extended itself beyond its original aim of being a decolonial, queer, feminist, and norm-critical space and has become an indispensable resource for the Art and Cultural community, and we have created relevant critical discourses not only within our aims to be a decolonial, queer and feminist values, but also extended ourselves into becoming a space for the voicing of marginalised and radicalised bodies.

Currently, I am the co-Artistic Director of Museum of Impossible forms with Marianne Savallampi, and we are responsible for the overall programming, managing our multilingual library, an ongoing archive, curating the workshops and events, making the coffee, maintaining the space and its day-to-day functioning, liaisoning with invited artists and performers, offering technical and documentation support, as well as managing finances and accounts. We work with m{if} members and invited artists, who lead specific weekly or monthly projects. Through our curatorial focus in 2019-2020 titled, “An Atlas of Lost Beliefs (For Insurgents, Citizens, and Untitled Bodies)”, we have made significant interventions through cinema, performance, music, spoken word, discourse, visual arts and activism-based practice, discourse, and pedagogy.

One of the most important reasons for founding a space such as this was to be able to offer a platform of critical, artistic, curatorial and cultural engagement for artists and audience alike – a possibility of a space that others of my generation and I didn’t have in India.

For me, the word museum already contains within it the contemporary notions of the para-museum, the counter museum, the anti-museum. A Museum must be – and M{if}is – a space in flux, one that transgresses the boundaries or borders between art, politics, practice, theory, artist and spectator. It is a contested space, a space of unlearning, which is the challenge for M{if}. This is the impossible in Museum of Impossible Forms: the ‘para-institution’ – a space that acts neither within nor against traditional institutions, but alongside them.

And so, museum building as a critical artistic praxis means to utilise and often subvert institutional methodologies and power, to apply this power towards the eradication of power and contribute to the questioning of dominant hegemony. This remains the essence of my overall practice as an artist across all the projects I am involved with.

Is there any particular medium that overpowers the ease with which you express yourself? If so, why?

AM: One can say my favoured mediums of expression are ‘online materials’ and ‘digital tools’ – something my generation of ‘digital natives’, who grew up with personal computers, wireless telephony, and electronic retrieval systems of every size and scale.

The translation of any substance into an immaterial form is the basic parameter of the lifeworld we inhabit. With it comes the understanding that data “flows” rather than being confined, and that images and episodes are part of ongoing narratives rather than guarded pools. My projects aim to create open-source, free, post-democratic platforms of knowledge and I am continuously exploring how such platforms can become politically conscious archives of the future. These politically conscious archives of the future which I refer to as “knowledge systems’ seek to produce knowledge, and as such are enmeshed with varying methodologies of research and engagement.

Before beginning a project, I first identify its social, political, and cultural needs and the gaps that require attending to. Once they are identified, I begin research by collecting, learning, and investigating to form the building blocks of the archives that will structure the overall vision of the project. My collected materials are rooted in datafeminist, posthumanist critical theories of making visible hegemonic power relations and silenced historical materialism.

How does the preservation of material and emotional history in the present through futuristic channels hold together the relevance of your work?

AM: In a world mediated by technology, archives, whether physical or virtual, are shaped through our performative actions and understanding of the world around us, and when archives inform us, they contain a performativity of their own. This two-way relationship, a defining feature of contemporary social culture, can be understood under the header of cybernetic feedback loops. Through my projects combining archival work, bookmaking, data mining, drawing, material research, new media works, photography and video, research, and published texts, I outline the mutual interactions and interrelated performativity of archives and its users, arguing that this collective responsibility induces knowledge systems into becoming politically conscious future archives.

I am a transmedia artist, I create immersive cyber archives and I love science fiction. Beyond the usual futuristic narratives of classical science fiction, what fascinates me the most is its ability to reveal disturbing truths of our contemporary realities and current timeframes through very human and posthuman stories. I gravitate towards utilising this characteristic of science fiction in my projects to map narratives of history, memory, and identity through a multifocal lens of violence, conflict, and trauma.

What would be the process that goes behind a performance by you?

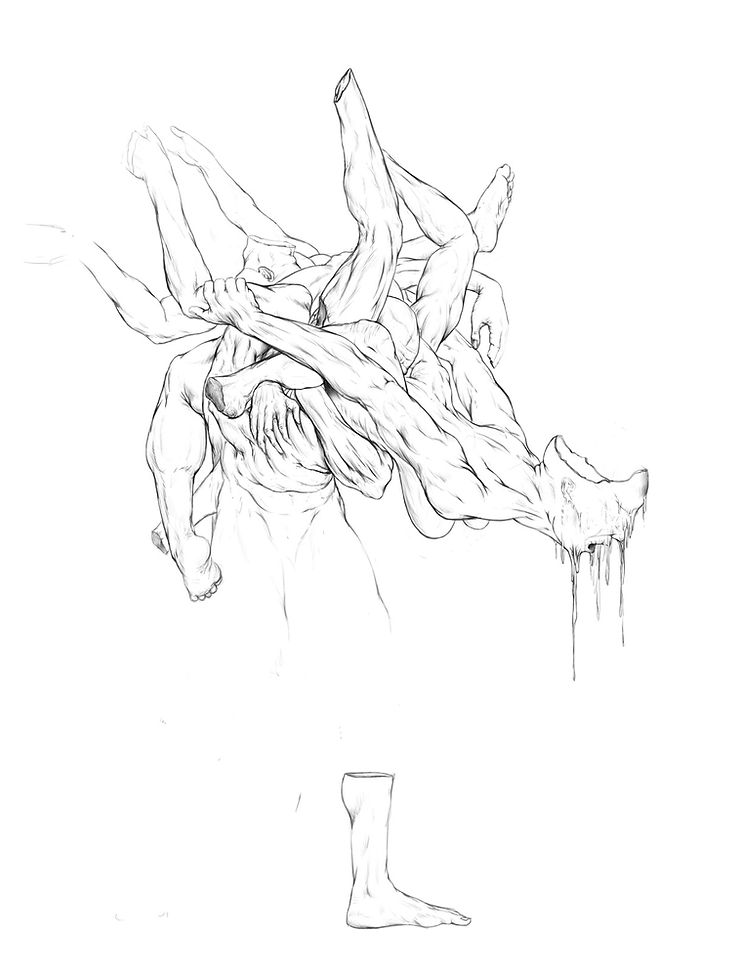

AM: Situated in specific conceptual foundations, my performances can be broadly categorised into ‘body performances’ and ‘performance of networks’.

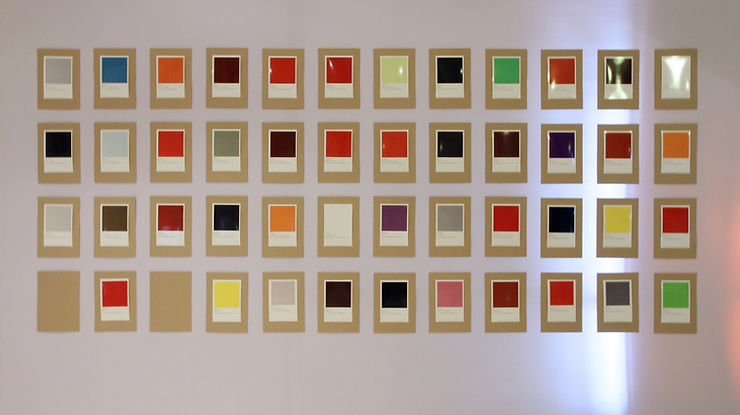

My project ‘256 Million Colours of Violence’ is a ‘performance of networks’, where asking participants to fill out an online survey form, is to ask them to confront the paradoxical nature of identities, experience the fact that identities are complex social constructs and that their identity is by no means ‘mainstream’ or normative. As a site of negotiation and inviting active participation, the project reshapes the individual online experience into an emotionally charged private performance of confrontation and healing.

Performances such as Narrating WAR constitute a more traditional understanding of a performance, but is also based on extensive archival research. The Performance is a reading of a comprehensive and ongoing list of all ‘wars, battles, sacks, sieges, revolts, revolutions, bombings and insurgencies’ from 3000 BC to the present, formulating a history of conflict spanning 5020 years. The research for this has been ongoing since 2014.

My performances in this sense are primarily about setting the stage for further dialogue, and to transform research into potential poetic experiences, where “even horror can be lived out in poetry”. This is not to say that poetry weakens or diminishes horror – what it perhaps means is that poetry translates horror to that level where, lived out through poetry, it is no longer degrading.

All performance projects involve months, often years of research, planning, building a team, collaborating with art spaces, raising funds and their execution.

Has your stream of consciousness ever reflected itself in creating a work of art? If so, what are the factors that have been touched by it?

AM: Personal stories are often at the core of several works that I am engaged with. Whether in my earlier paintings or the current archival projects, I believe that one’s own worldview, ideologies and belief systems are inadvertently bound to enter an artistic practice – I assume this is also true of most artists.

I was an introverted child and have grown up with dyslexia. Since the early years of my practice, the choices of what to paint or why to create images of violence were rooted in these formative years. These experiences fuelled my desire to make sense of my identity as an outsider, an atheist born in a Muslim family, and to be seen as such. Once I accepted that identities are never pre-given but that they are always the result of processes of identification, and that they are discursively constructed, the question that arises is, ‘What is the type of identity that critical artistic practices should aim at fostering?’ Today, the practice itself may have transformed its medium but the dynamics of hegemony, the politics of power relations and the ways in which issues of identities affect everything are still the red threads running through my artistic practice. Having said that it is undeniable that my works reflect also my love for classic rock music, science fiction, food and its politics, and glitch-noise music.

As a citizen, I am sensitive to privileges and power relations embedded in our capitalist social structure and critical of its structural oppression. An individual’s own worldview, ideologies, belief systems inadvertently are bound to enter their artistic practice. I believe this is also true for me. Personal stories are often at the core of several works that I am engaged with – whether through my earlier paintings or the current archival projects that I am developing.

While the maze of learning and unlearning bears no end in the contemporary arts, Ali Akbar Mehta is one of the few who choose to relentlessly find new avenues and allow it to keep expanding. From a distance, the many colours and categories that divide his body of work paint him as a prism, with diversity shining on the other end, and it is safe to say that the journey produces a deeper meditation up close.