“My Friend, you would not tell with such zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory/

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori

-Wilfred Owen”

Monarchs, dictators and elected governments have always relied on the Arts to garner popular support for their war efforts. Time and again, literature and artworks have been officially employed by the state to glorify the act of dying for one’s country on the battlefield. The Latin quote by Horace – “Dulce et decorum est/ Pro patria mori”, does the same; it presents the act of dying for one’s country as ‘sweet and fitting’. However, just as the poet (and soldier) Wilfred Owen makes us see the emptiness of this quote, artists at different points in time have challenged this war propaganda and made us literally see the gruesome reality of war. These artists refused to be bemused by the illusion of war and dared to say things through their art that very few were willing to utter.

Art Fervour presents to you a list of these artists who responded to war in their artworks. Marked by both their individual experiences of war and their specific artistic choices, these artists’ responses to war rewind, reflect and review the ‘horrors of war’.

Image courtesy: Wikipedia

1. The Apotheosis of War

The Apotheosis of War is an oil on canvas painting by the Russian war artist Vasily Vereshchagin. Following the completion of the painting in 1871, Vereshchagin dedicated the work “to all great conquerors, past, present and to come”. The painting depicts a pyramid-like pile of human skulls on a banner landscape, with a flock of ravens picking over the skulls. In this painting the artist emphasises the immense loss of human life that a war results in. Vereshchagin had not only witnessed the reality of war but also participated in one. In 1868, he was a part of a Russian garrison defending the Samarkand fortress against the troops of the Emir of Bukhara. The bright colour palette of the painting sits in contrast with its dull and gloomy theme, specifically to draw the viewer’s attention. However, the painting received hostile reactions in Russia for representing the army in bad light and was therefore prevented from being shown at Vereshchagin’s exhibition. Now displayed at the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, this painting has become a bare-faced symbol for the savage truth of war.

The pyramid of skulls is a reference to Mongol conquerors who displayed the skulls of their enemies in a similar fashion.

Image Courtesy: Museo Nacional Centro De Arte: Reina Sofia

2. Guernica

26th April 1937 had been a regular Monday until 4:30 P.M. when German warplanes began appearing in the sky above the small Basque village of Guernica. The planes were there on behalf of General Franco’s fascist regime as a macabre rehearsal for the blitzkrieg tactics of WWII. For over 3 hours 25 minutes bomber planes dropped 1,00,000 pounds of explosive, reducing the village into a rubble and killing one-third of its entire population. This human suffering led Pablo Picasso to paint the sensation of the 1937 Paris International Exhibition, Guernica

An important aspect of Guernica is the density of human suffering depicted in the 11 X 26 feet mural that jarringly awakens the viewer to the tragedy of the predicament. The woman holding a dead child screaming towards heaven, the dead soldier with disjointed parts, the terrorized horse and the burning woman, all attempt to bring human suffering to the centre-stage.

Image Courtesy: Wikipedia

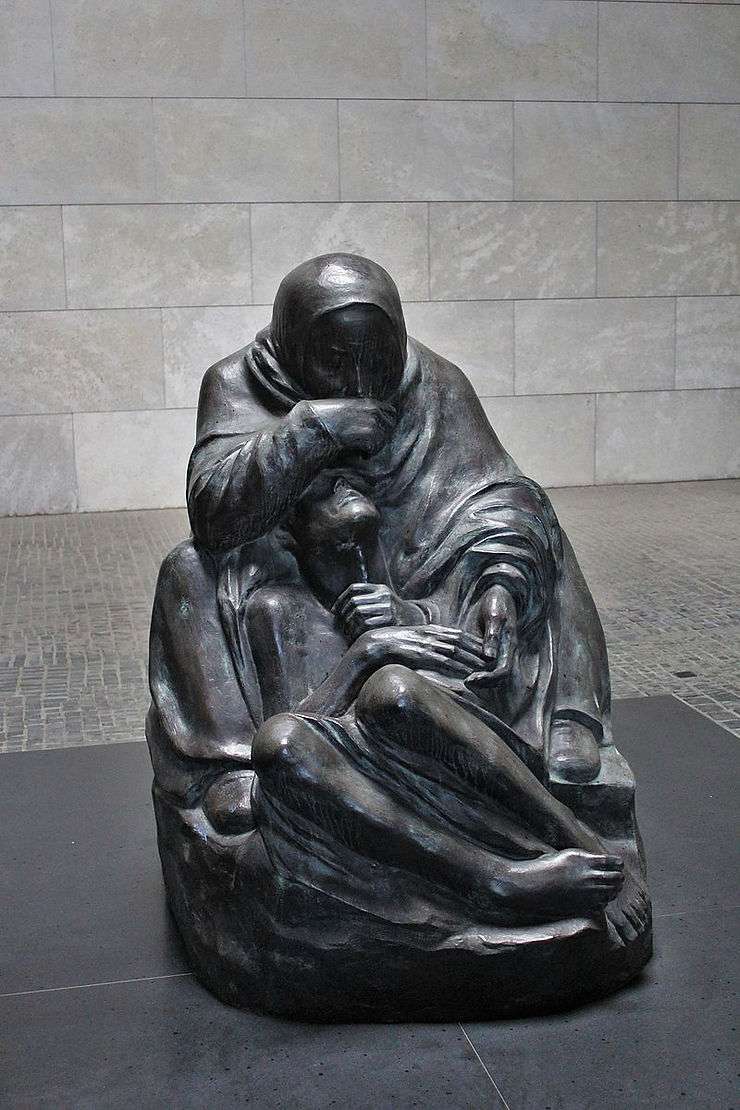

3. Mother with her Dead Son

Initially a supporter of war, Kathe Kollwitz gradually realised the hollowness of the promises made by the war. Swept up by the patriotic sentiment of fighting for the fatherland, Kollwitz got her sons enlisted at the beginning of World War I. However, after she lost her younger son Peter on the battlefield in October 1914, Kollwitz began to consider the immense sacrifices that the war demanded. The sculpture Mother with her Dead Son was made by Kollwitz in 1937 or 1938 and is dedicated to Peter. Inspired by the classic Pieta, the sculpture depicts the dead son in his mother’s lap. But unlike Pieta where the body of Jesus rests on the knees of Mother Mary, in this sculpture the dead son lies crouched on the ground between his mother’s legs. Like other works by Kollwitz, this sculpture presents the losses that families suffer at a personal level because of the lives that the monster of war swallows. Kollwitz’s work is a personal response to the losses suffered during the war, that makes the war statistics more than just numbers.

Check Kathe Kollwitz’s woodcut The Parents that conveys the profound grief of those who lost their child in war.

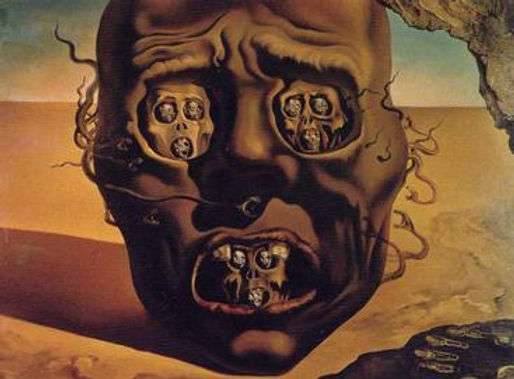

4. The Face of War

The Face of War is an oil on canvas painting produced by the famous surrealist painter Salvador Dali during World War II in 1940. The painting depicts a large, frightening face which metaphorically stands for the ugliness of the war. This face seems like a skull or the face of a corpse, and is shown floating on a desert. The eye sockets and the mouth opening of the face are filled with three smaller, similar faces, indicating that the suffering caused by the war is continuous. There are also many snakes surrounding the face, and a handprint in the bottom right corner. Further the brown tonalities of both the face and the desert heighten the sense of horror evoked by the painting.

Inspired by the war, most of Dali’s paintings reflect on the catastrophes that war causes in the lives of people. In this painting, as the title suggests, Dali imagines the face of war in his surrealist style. This face is scary, mournful and almost dead. Displayed in the Museum of Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam, Netherlands, this painting allows its viewers to come face to face with the horror of the war.

The handprint at the lower, right corner is a true impression of Dali’s own hand.

Image Courtesy: Imperial War Museums

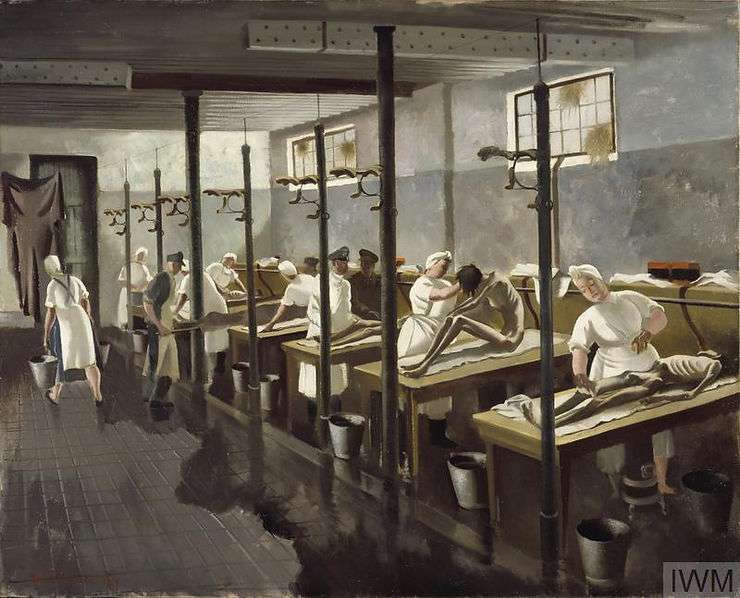

5. Human Laundry, Belsen: April 1945

In 1944 Doris Zinkeisen was commissioned by the Red Cross and St John War Organisation to record their work in North-West Europe. Zinkeisen was one of the very few women war artists to be sent overseas for this project. In 1945, Zinkeisen arrived at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, soon after its liberation by British soldiers. Human Laundry is one of the artworks produced by Zinkeisen during this time and communicates the scene of absolute horror that Zinkeisen encountered at the camp. The painting depicts a line of wooden tables with feeble figures sitting or lying on top, attended to by men or women dressed in white. There is a metal bucket at the foot of every bed and a woman can be seen carrying two buckets out of the room. The ‘human laundry’ was a stable at the camp where German nurses and captured soldiers cut the hair of inmates and bathed them before they could be transferred to the hospitals run by the Red Cross. The tension of the painting lies in the contrast between the feeble bodies of the inmates and the well fed, rounded bodies of the German nurses. This contrast in body compositions, allows Zinkeisen to bring to attention the crimes Holocaust committed upon the bodies of millions.

In another painting from this series, Victims of Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, Zinkeisen depicts the ghastly sight of skeleton bodies just flung out of the huts.

Image Courtesy: Banksy Explained

6. Bomb Hugger

Bomb Hugger is one the most daring stencils by Banksy on the theme of war. The stencil shows a ponytailed girl hugging a bomb as if it were a teddy bear. The juxtaposition of the innocent child and the dangerous bomb, increases the sense of danger felt by the viewer. Here Banksy seems to indicate that large democracies are buying and selling bombs as if they were toys. On the other level the stencil can also mean that the forces of love and innocence can overcome the forces of violence. This artwork speaks directly to those in power, questioning the huge budgets allocated to military warfare.

Image Courtesy: Free York

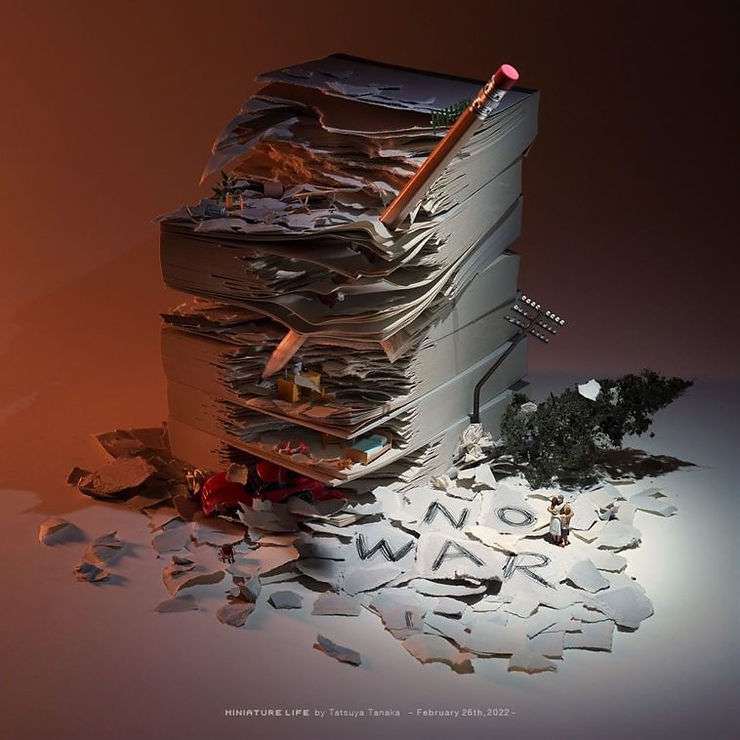

7. NO WAR

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine rages on, many artists have responded to this crisis through their creative works. NO WAR is one such creative project by contemporary Japanese artist Tanaka Tatsuya. Using his signature miniature scale, Tatsuya has employed daily objects like paper and pencil to convey the destruction caused by the war. The stack of paper has been presented as destroyed buildings and the pencil as a piercing missile. Below the stack of sheets, among the scattered pieces of paper are words ‘NO WAR’ written. Next to this writing is a soldier who hugs his wife goodbye. This use of ordinary objects makes the devastation of war feel more real and near home. Moreover, the use of miniature style to depict the damage caused by the war draws specific attention to the extent of destruction.

From inability to work with the conventional style to the metaphorical face of war; from personal expression of war tragedy to a powerful idiom of street art—artists across time have responded to war in different ways. Each of these artworks rewinds, reflects and reviews the horrors of war, in the hope that the citizens will not give into the lie that dying in war is ‘sweet and fitting’.

Let us know about other artists who respond to moments in war in their artworks. For more such thematic exploration into art history, check our editorial page.