‘In winter, when I put a quilt over myself, its shadows on the wall seem to sway like an elephant. That sends my mind racing into the labyrinth of times past. Memories come crowding in.’

– The Quilt, Ismat Chughtai

Kamlesh Devi from Himayunpur, Najibabad, a mother of three, is often found smoking her hookah under a jamun tree in her courtyard. She loves storytelling and singing bhajans while she sews, even though she forgets a line or two once in a while. Her bhajans had charged the air at the home in Najibabad where twenty other women sang along while sewing on a seven metre long scroll in remembrance of embroidered quilts that used to be gifted during weddings.

Closed Doors

When the whole world was terrified to step out of their homes due to the pandemic, women in some areas of the world were terrified of staying in, owing to the domestic violence at their homes. Human lives were claimed not just by a virus but also the atrocities inflicted on women in communities across the world.

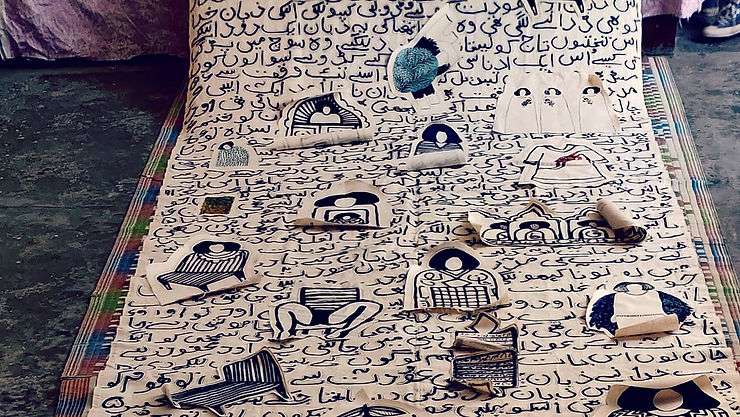

Moved by the plight of struggling artists due to the pandemic, several artist communities (based nationally and internationally) have initiated community arts projects to bring in financial aid, to promote the work of artists whose practice had suffered due to the pandemic and for several other objectives. One of those projects was recently unveiled by Arshi Ahmadzai at the Max Mueller Bhavan, Delhi. An artist herself, Arshi led nearly 20 women for almost 9 months as they created a painted and embroidered scroll that carries artworks which symbolize fragments of the lives of these women, including Arshi.

Not just a ‘Quilt’

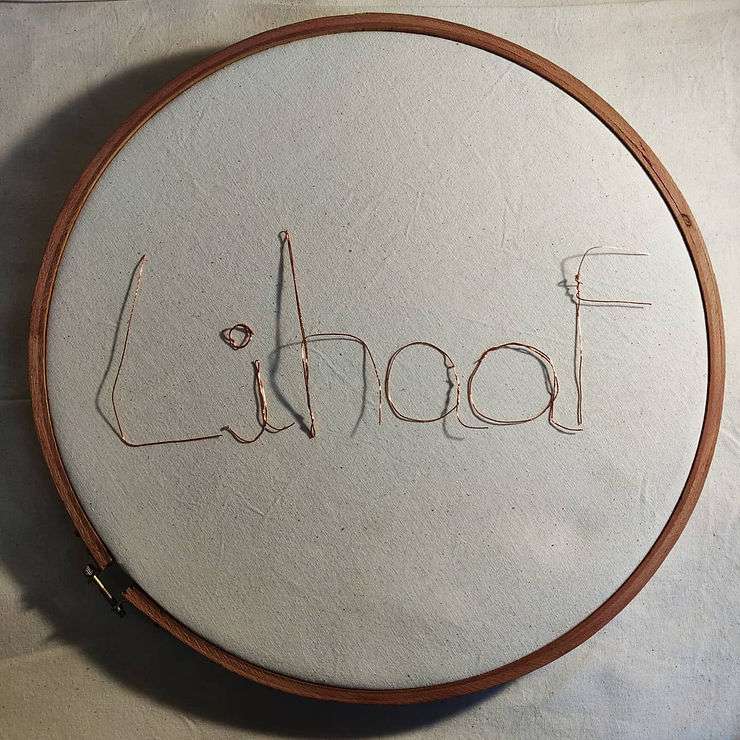

‘Lihaaf’ is the Urdu word for quilt. A quilt is essentially an embroidered blanket with layers of textiles patched together. In the Asian context, brides used to embroider quilts and pillowcases as part of their wedding trousseau. Arshi transformed it into a community art project that focuses on the agency of women in their homes.

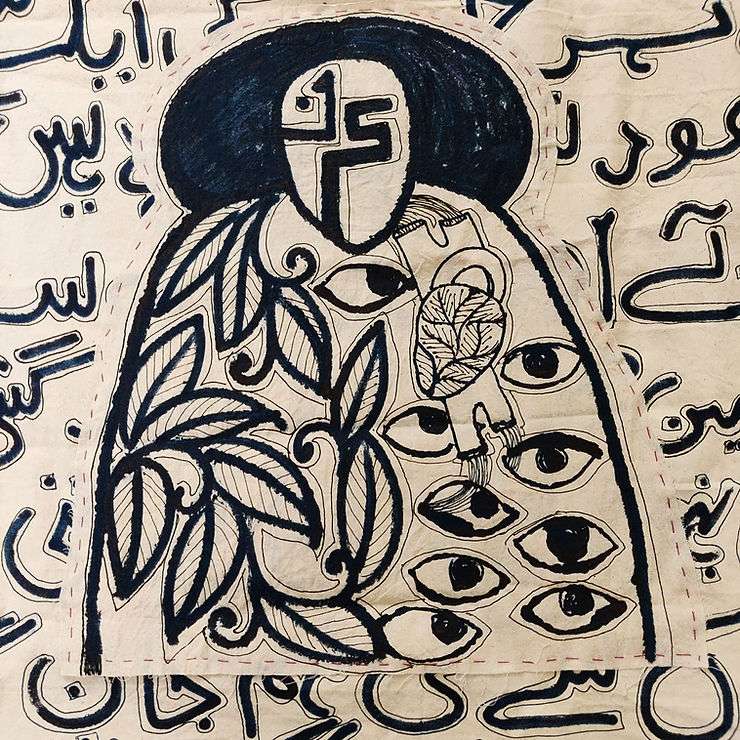

Realised within the framework of Five Million Incidents (2019-20) and conceived by Goethe-Institut/Max Mueller Bhavan in collaboration with Raqs Media Collective, Lihaaf- The Quilt brought together twenty women from Najibabad where they engaged in a creative process and expressed their respective stories through drawing, poetry and embroidery. The women belong to the Nat community. As they sewed patches of drawings on the seven metre scroll, they recited poems and sang bhajans.

The Lihaaf project that shares the same name as a short story by Ismat Chughtai, was conceptualized by Arshi by drawing on the injustices imposed on women within their communities and homes. Being a part of the Najibabad city herself, Arshi has channelized her art practice towards reflecting on the lives and struggles of women who have lost the ability to express themselves with time. She believes that art should be created in the service of society and not in isolation. This idea led her to make Lihaaf a collaborative experience. The first phase of Lihaaf was carried out in a secure home at Najibabad, a city known for its Rafugari or the craft of darning. The second phase was completed at the Max Mueller Bhavan at New Delhi.

A Fabric of Narratives

Driven by the orthodox norms of the society, these women had stifled their inner desire to express and create. Other than home management and child rearing, they had ceased engaging in activities that required the employment of their intellect rather than their bodies. The Lihaaf project stirred that desire leading them to create artworks that they never would have dared to ponder upon.

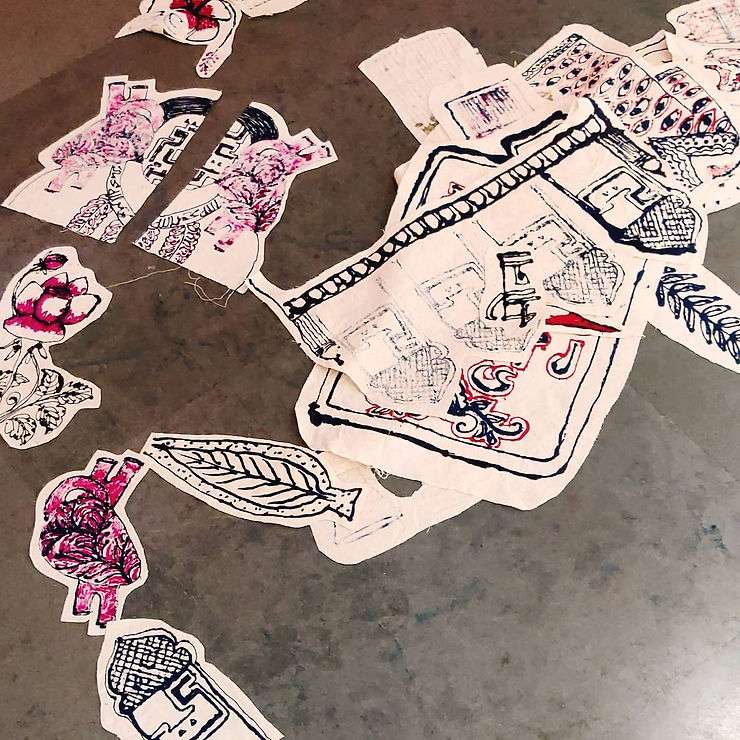

The scroll contains the writings of numerous ancient and contemporary female poets and writers. Initially, Arshi had asked the women to embroider a pattern of their preference. They were trained rafugars who had also worked on kani shawls. However, when it came to portraying their own thoughts they were hesitant. So she provided them with reference images which they could improvise and work upon. Guided by her visual imagery they embroidered patches of fabric with women represented as trees, chairs, doors, figures and flowers.

Snippets from Lihaaf

Nasreen Begaum, a mother of six loves to listen to mushaira while she cooks. She can often be found reciting couplets of Rahat Indori sahab. She decided to contribute to the Lihaaf project because it gave her an outlet for expression, as well as a chance to explore the lives and stories of other women.

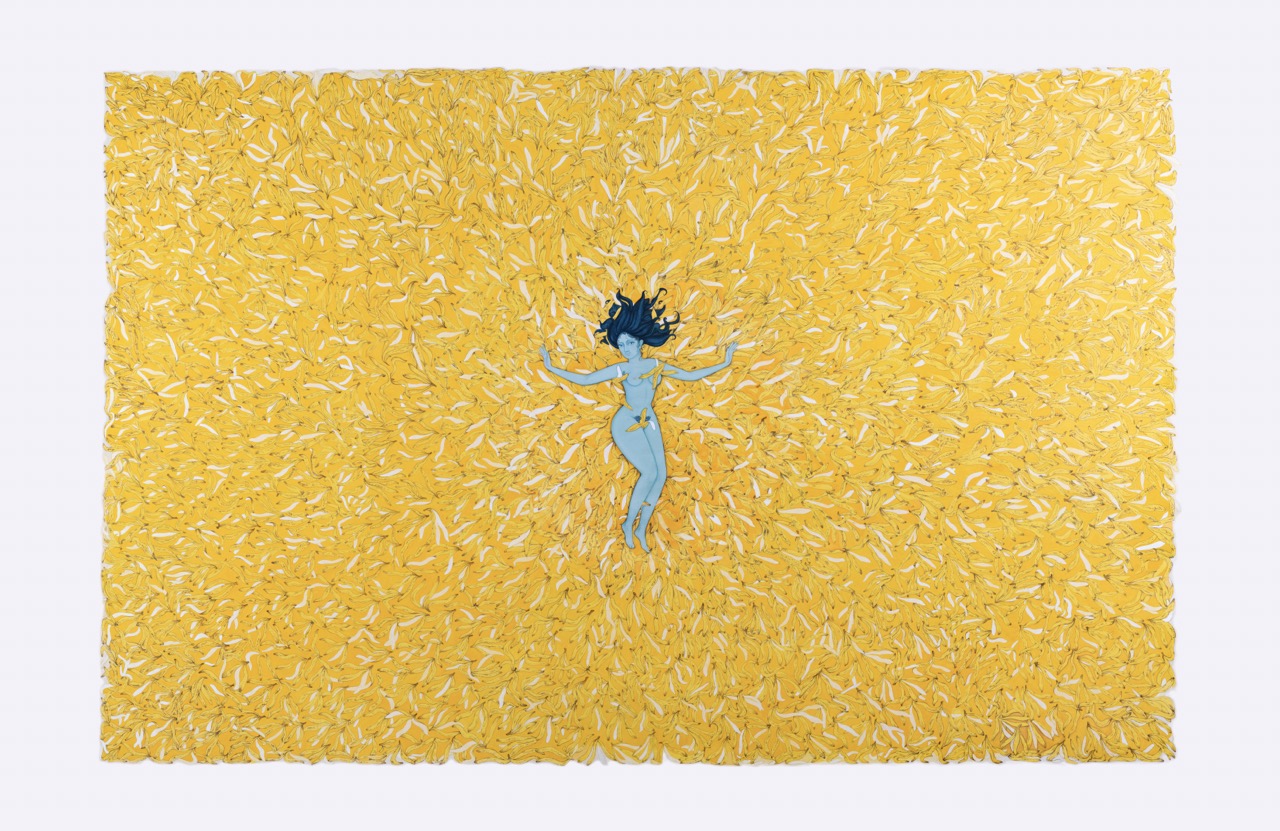

For Nazra Parveen, her paintings are a reflection of her dreams and hopes. Having to quit her studies and support her family upon her father’s death, Parveen’s art has served as an escape and respite from her harsh reality. Parveen’s patchwork of bold strokes and vibrant blues, for instance, is an ode to the free world she hopes to live in someday, free of fear and judgement.

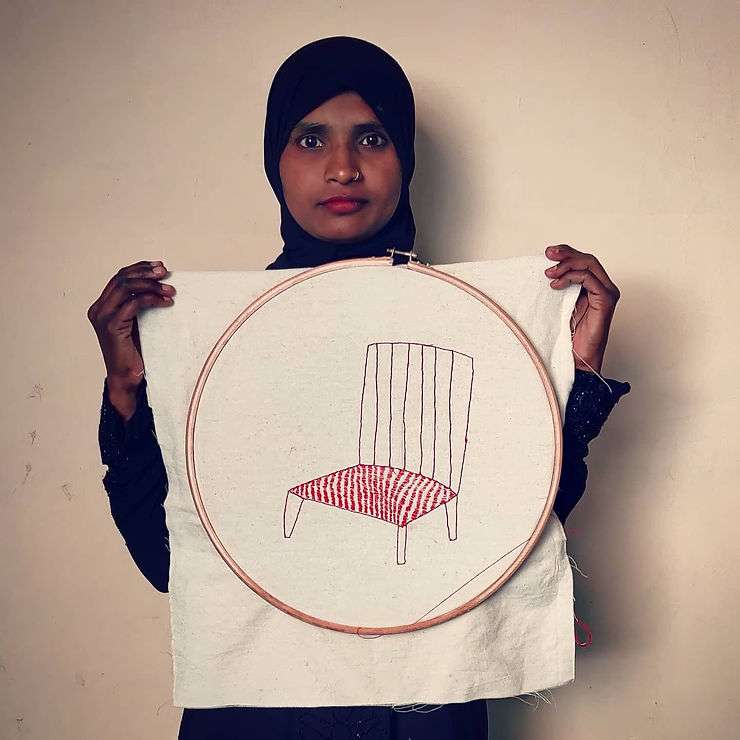

Halima, at 26, is a single mother of two children. A victim of domestic abuse, Halima is determined to ensure her daughter gets a good education so she can be financially independent in the future. But raising two children, while being the sole breadwinner for her family is no easy feat. She expresses this exhaustion in her embroidery of a simple chair, that signifies a moment of rest and respite from the drudgery of everyday life.

Razda Parveen, Nazra’s mother, determined to not let her daughter be the only one bearing the burden of supporting the family, runs a cosmetics store. But times have been tough and it’s barely enough to keep them afloat. Like her daughter, she too contributed to Lihaaf in the hopes of getting acquainted with other women and joining an informal network of working women like her. Added to that, the remuneration they received for their contribution was of considerable help to their family.

Roushan Jahan is one of the many women contributing to the Lihaaf project, for whom the project has served as a welcome escape from the travails of everyday life. A shy woman from Humayunpur, Roushan Jahan was married at a very young age and has since had very little opportunity to explore life outside her family. Working in collaboration with other women on Lihaaf not only gave her the chance to meet and interact with different women from different walks of life, but also time to look inwards, explore an interest of her own and develop it; a chance to create something fulfilling to herself other than looking after her home and family.

Lihaaf meant differently to each of the women involved in it. To some it stood as a means of income or an escape from a life of drudgery and to some it presented as an opportunity to be a part of a larger and an entirely different kind of artistic endeavour for a short period of time. For a very short span of time, they were lifted out of the role of a homemaker, breadwinner, wife and mother.

A Journey in Thread

Lihaaf was supposed to be exhibited in April this year. However, owing to the pandemic the process was delayed. The scroll along with the embroidered patches of fabric exhibited at the Max Mueller Bhavan went live on 5th November, 2020. The entire process of making Lihaaf has been documented visually and textually by Arshi and Five Million Incidents on Instagram along with fragments from the life stories of these women and their eight month long journey of collaborating on Lihaaf.

Arshi’s personal experience of growing up in a patriarchal, orthodox society of Najibabad influenced her to dedicate this project to those women who have attempted to keep the voice of oppressed women alive and resonating.

It is not very often that art enthusiasts get to witness an artwork that encapsulates segments of feminist literature and a tangible visual narrative by a marginalized collective of women. Lihaaf is one of those rare artworks that originated out of a process driven by suppressed artistic expression and represents the cultural consciousness of a small part of the oppressed female population of India.

Five Million Incidents is a year long series of events conceived by the Goethe-Institut/Max Mueller Bhavan that invites experimentation with the possibilities of public space, time, media, communication and interaction. The program aims at expanding the notion of the audience regarding art as an extension of the everyday experiences in life. It conducts open calls applications for visual arts projects that attempt to bridge the gap between the disciplinary process and the ordinary activities of daily life.

All records of the background stories of the participants and image credits go to Arshi Ahmadzai.

Read more about similar interactive art projects by self-driven artists here.