By the time the Medici, an influential family of bankers and the de facto rulers of Florence found their hold on the city waning, scores of artists had found a place of prosperity under their long arms. This tradition had begun when the talented teenage painter Domenico Ghirlandaio caught Lorenzo de’ Medici’s eye.

Ghirlandaio had many young apprentices; several were compelled by poverty to be bound to his workshop. In 1489, Lorenzo asked Ghirlandaio to provide him with two of his best pupils, one of whom Lorenzo took to much greater fancy. Realizing his unusual talents, he proposed that the artist move into the palace and live there as his son to be educated along with the Medici children.

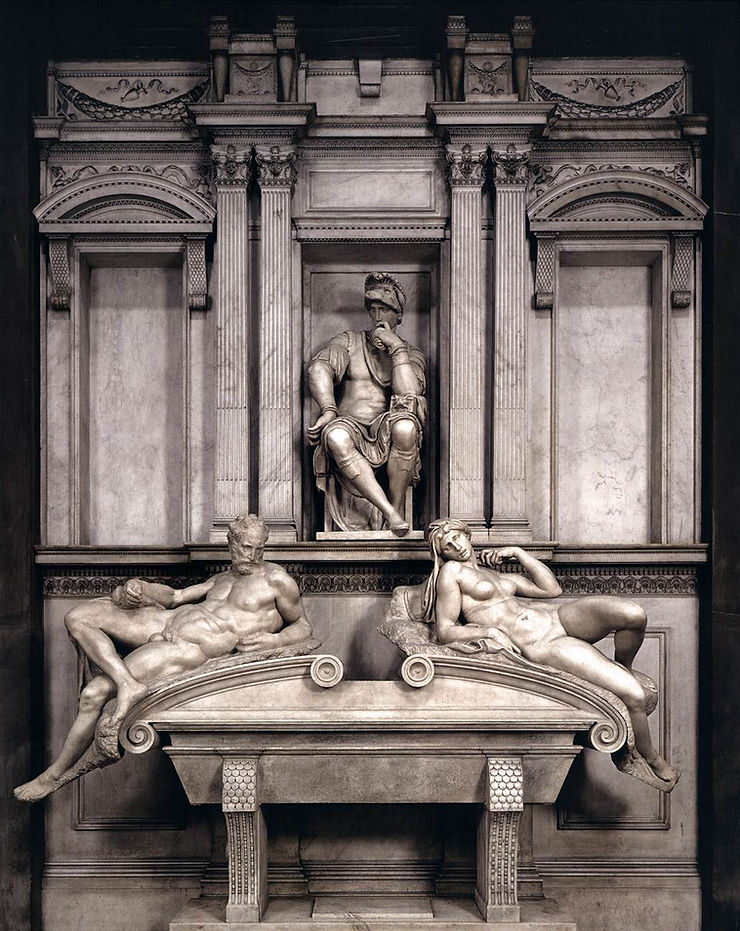

Lorenzo provided an atmosphere of support and sponsorship that resulted in the artist’s interest in poetry, science, philosophy, and art. He came to attend the Humanist academy and absorbed the spirit of the Renaissance through direct contact with philosophers at the Medici court. Even the Medici papacies of Pope Leo X and Pope Clement VII commissioned the artist to make monumental tombs, sculptures, and paintings. By the time the Medici found their influence on the decline, the artist had found his solid footing, all thanks to Lorenzo ‘the magnificent.’

The artist was Michelangelo, and Lorenzo’s actions went beyond the interests of an ultra-rich influencer. In Lorenzo, Michelangelo had found himself a patron.

Who is an art patron?

The idea of a patron served a fundamental function in an industry that is remarkably famous for being a notorious place to gain wealth quickly (the idea of a ‘struggling’ and ‘starving’ artist is no joke). Patrons were not just consumers of art, but financial support systems, often dictating the form and content of art made.

It wasn’t just money, however. It was money and influence that mattered: art patronage functioned as proof of wealth, status, and power and could serve purposes of propaganda and entertainment. Quite simply then, this meant that the earliest patrons of art were the creme de la creme of society, aristocrats, royalty, and/or important members of religious institutions – but today, this idea has undergone a decisive change, as have the number of aristocracies.

While by no means an exhaustive list, here’s a quick highlight on the personalities that have sustained the growth of art.

Cradling civilization through ancient patronage

The ancient world was not divorced with the idea of patronage. It is no secret the central position the art of these cultures (especially classical Greece and Rome) have had in the world of art. So it isn’t surprising when we come across powerful names that actively supported the creation of such art.

Art in the ancient (and also medieval) times was made by guilds. The members of these guilds didn’t identify themselves individually; and consequently, whatever names we have with us today are certain proofs of their importance, even if the information remains scant.

This is foremost true for the Mesopotamian ruler Gudea, who only ruled a section of Sumeria for merely twenty years, yet left us with an indelible impression of his patronage. Twenty-seven statues of the king have been found today in a land that otherwise remains empty of art. These were carved from an expensive and rare material, diorite – a dark stone that the Egyptian pharaohs used to render their portraits immortal.

His patronage wasn’t the only that left him with an impressive legacy – the Pharoah Hatshepsut of Egypt was another personality that consolidated her authority through art. Hatshepsut ruled a highly conservative society where women weren’t ‘supposed’ to lead. Cautiously, Hatshepsut commissioned numerous sculptural portraits that represented herself in the guise of a man (surviving examples sport a beard, kingly male garb, and a lack of breasts).

In fact, her legacy lives in the import of precious materials like malachite and ebony that were used by Egyptian artisans in their art, ultimately laying the foundation for subsequent development of Egyptian art.

Sponsoring nobles and medieval patrons

In the early 1480s, Leonardo da Vinci wrote a ten-point letter to Ludovico Sforza, the then de facto ruler of Milan, seeking a job at his court. Sforza was looking to employ military engineers, and Leonardo highlighted his abilities as an architect and designer that would aid Ludo. Interestingly, he only merely hinted at his artistic capabilities, but that didn’t matter – he was accepted for the job.

In a fate similar to that of Michelangelo with the Medici, Leonardo spent seventeen years with the Duke, who commissioned some of his greatest works in art(The Last Supper, for one).

Several women were also powerful patrons. Known as the ‘First Lady of the Renaissance,’ Isabella d’Este was primarily responsible for turning the city of Mantua into a Renaissance hotbed, and also entered into influential contacts with artists like da Vinci, Raphael, Titian, Bellini, etc. She provided patronage to her fellow artists and converted her apartment into a museum to showcase the art made by ‘her’ artists.

It wasn’t just Europe – the Empress Consort Tofukumon’in of the peaceful Edo period also played a pivotal role in the development of an aesthetic culture of Japan. Wielding her own former Tokugawa influence, she rebuilt prominent Kyoto temples, wrote poetry and calligraphy, focused on textile art, and collected ceramics by famed artists.

New trends in art and patronage

By the 19th and 20th centuries, a decisive shift emerged – if medieval nobles provided patronage to the artist, well, there hardly remained such nobles to continue the same. Now, great art academies fostered artists and their growth.

It was the realist painter Gustave Courbet’s charge against the French Academie des Beaux-Arts that provided the new kind of patronage that would be seen from here on. Recognized as the first instance of an independent exhibition by a solo artist, art patronage now would embody the idea of artistic self-sufficiency. The Impressionist painters were the next in line to break away from academic patronage.

With the rise of such artists, individuals flocked to provide patronage(and also to solidify their position). Gertrude Stein’s position among the avant-garde artists in Paris was a testament to her patronage: through collecting art, she acquainted herself with the bohemia of artists such as Cezanne, Matisse, and most famously Picasso. Their friendship and her subsequent patronage directly propelled his career until he achieved international acclaim.

Slowly, numerous names started cropping up. Even before his advertising fame, Charles Saatchi began collecting art and found a connection with the Young British Artists, for whom he was a key patron (Damien Hirst was found patronage under him). The same force was brought with Peggy Guggenheim, and Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, and more famously, Jackson Pollock directly owe their careers to her patronage.

What does patronage mean today?

Certainly, we’ve come a long way since aristocrats provided their money and influence to the creation of art. Neither are all relations positive – the fallout between Rockefeller and Diego Rivera is just one example, but more importantly, patronage today appreciates the value of not just the art, but the artist. While earlier patrons dictated how the art should be made and what it should stand for, patronage today is about the creative liberty, independence, and growth of the artist in its pursuit.