What comes to your mind when you think of the Indian freedom struggle – protests, marches, shouting, slogans, non-violent activism and jailed comrades perhaps? Loud and roaring action is an intrinsic feature of any movement. But it’s only one part of the story. Such action is always preceded by quieter, gentler and more restrained acts of rebellion. But these are no less powerful.

It is the poets, writers, painters, musicians, oral storytellers and other custodians of culture who transmute what’s in their hearts through their art and in the process revitalise the collective soul of the people they are looking to inspire. Because the truth is that people are moved to action when they are moved. To answer the question of what moved our freedom fighters to fight without fear of consequences, ask yourself what moves you to care about the causes you care about.

On the occasion of India’s 73rd Independence Day we take a look at three Indian artists who were integral to the freedom struggle. It’s said that the pen is mightier than the sword. But so is, it turns out, the paintbrush.

Abanindranath Tagore and his humanised depiction of India

In 1905 Lord Curzon partitioned Bengal into two halves. It was supposedly done for administrative purposes but the real reason was to further the Raj’s divide and rule policy. This move sent shockwaves across the state and greatly agitated the people of both East and West Bengal. It was this incident that led to the inception of the Swadeshi movement. As the people sought to cripple the British economy by choosing to patronise homegrown goods over foreign ones, the nationalistic sentiment seeped into India’s art and culture as well.

‘Bharat Mata Ki Jai’ may seem like an everyday phrase today, but at the time it was quite unheard of. In 1873 Kiran Chandra Bandopadhyay wrote a play with the title Bharat Mata and in 1882 Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay introduced the phrase, ‘Vande Mataram,’ in his novel Anandamath. But apart from these two references, the idea of India as a motherland was a highly unfamiliar one.

Abanindranath Tagore, the nephew of Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore, painted Bharat Mata in 1906 to portray a humanised depiction of the nation, one that citizens could easily connect with. He painted her as a secular sari-clad woman holding four objects which signified food, cloth, learning and spiritual knowledge – attributes of nationalist goals.

Originally titled Banga Mata to protest the partition of Bengal, he retitled it to Bharat Mata so as to inspire people from all over the country to fight for their mother. Thanks to this painting, Bharat Mata entered the lexicon and became a rallying cry of the freedom movement.

Nandalal Bose and ‘Bapuji’, the symbol of resistance

On 12th March 1930 Mahatma Gandhi and 78 of his close aides began a march from Sabarmati Ashram to Dandi, walking 10 miles a day for 24 days. Along the way, they were joined by thousands of Indians. The march was to protest the prohibitively expensive salt tax imposed by the British and the unfair laws banning Indians from producing their own salt. The Dandi March is now celebrated in history books as an emblem of non-violent protest. But back then, before said history books had been written, it was a touching portrait by a master of the Bengal Renaissance that brought Gandhi’s act of quiet heroism to the people.

Nandalal Bose had said of Gandhi, “Mahatmaji may not be an artist in the same sense that we professional artists are, nevertheless I cannot but consider him to be a true artist. All his life he has spent in creating his own personality and in fashioning others after his high ideals. His mission is to make Gods out of men of clay. I am sure his ideal will inspire the artists of the world.”

Bose created a black and white linocut portrait of Gandhi walking with a staff and inscribed it with, ‘Bapuji, 1930.’ It perfectly captured the spirit of the event and of the quiet but powerful persona of Gandhi as the leader of a burgeoning movement. It went on to become the most iconic image of Gandhi ever created and a symbol of resistance and inspiration for the two decades of intense struggle to come. According to the Museums of India repository, ‘Bose was among the first to recognise that the image of Gandhi alone had the potential to unify a movement beyond the realm of a select few to express the collective will of a new nation.’

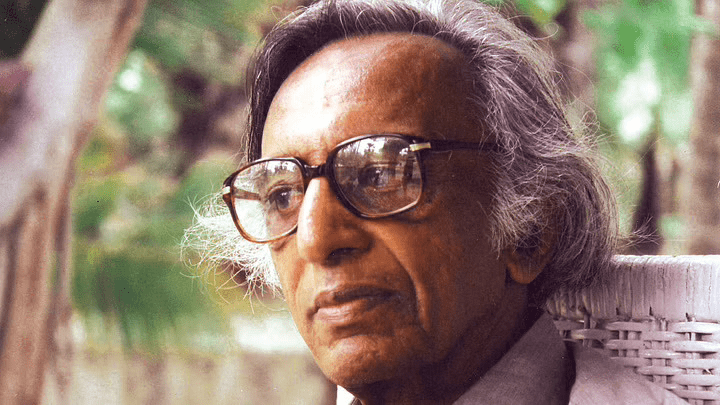

Zainul Abedin, the voice of the starving and founder of Bangladeshi-Modern Art

The Holocaust is an instantly recognizable chapter from the annals of history and the people who lost their lives to Hitler’s paranoid agenda of race purification are mourned to this day – as they rightly should. But far fewer people are acquainted of a tragedy of a similar scale that occurred around the same time as the Holocaust and claimed millions of lives. Though not a genocide, the circumstances that led to it were no less cruel.

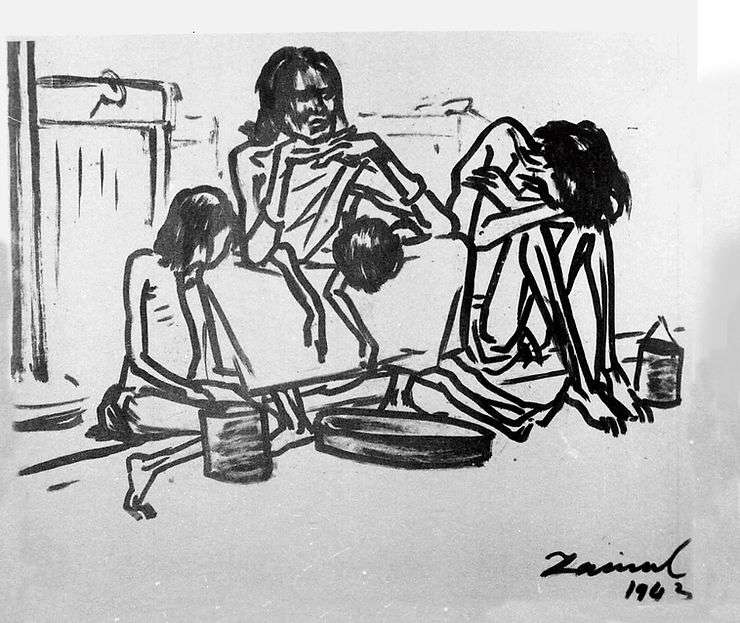

In 1943 Bengal was hit by a famine that claimed more than 3 million lives. The famine was a direct result of Winston Churchill’s war policies. While Indian soldiers and supplies were shipped out in abundance to bolster Britain’s cause in World War 2, there was little knowledge of the millions of nameless faceless natives dying thanks to the deprivation being imposed on them by the colonial government.

Zainul Abedin, who would later go on to be known as the founding father of Bangladeshi modern art, was then a twenty-something youth moved by the suffering he saw all around him and burning with a desire to do something about it. Armed with nothing more than a paintbrush he set about doing the only effective thing he could think to do – being a witness.

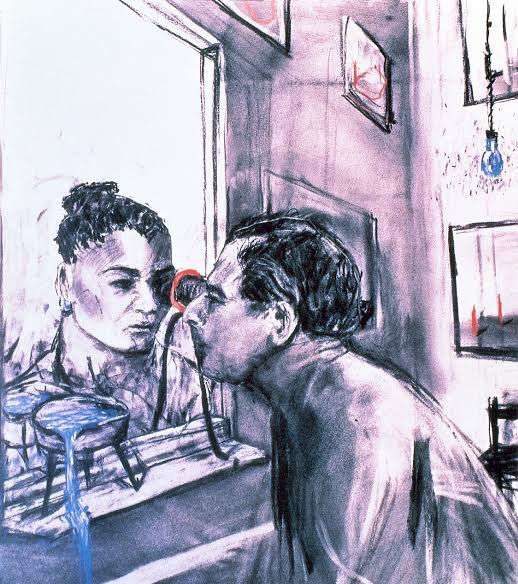

What followed are paintings in his acclaimed Famine Series. He burned charcoal to make his own ink and used cheap packing paper to bring to life the people starving by the roadside. Works like that of a young child desperately seeking sustenance from his emaciated, dying mother imprinted on the minds of the Raj’s subjects with a burning fury. The passion and anger that these skeletal, sinister images of starvation convey are far more effective than what words could have done.

His paintings pierced through the hearts and minds of Indians and contributed to the rage and anger they were already feeling. Sadly, Abedin was sadly displaced after Partition and had to leave India for Pakistan. But his haunting sketches of a forgotten genocide were instrumental in fanning the flames of nationalism back then and remain a chilling reminder of an unpardonable tragedy even today.