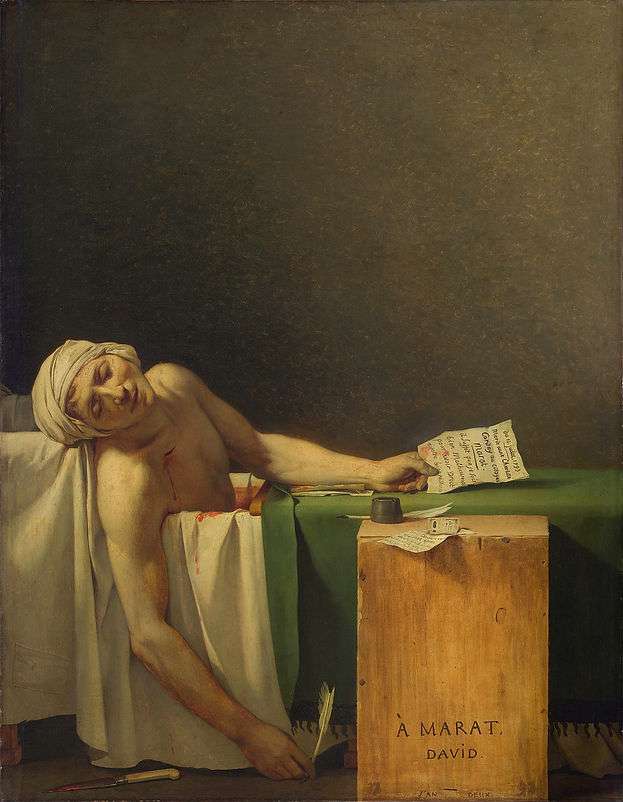

On the evening of July 13th, 1793, Jean-Paul Marat, a highly influential revolutionary of the French Revolution, was murdered in his bath. The culprit, Marie-Anne Charlotte Corday, a political rival and enemy of Marat, had gained entrance to his rooms on the pretense of providing reports of counter-revolutionaries; she found Marat in his bath and skillfully planted a knife in his chest. She didn’t flee the scene and was soon apprehended and guillotined.

Marat was a public-favorite for his ruthless way of dealing with aristocrats, and his companions saw his death a blessing for their propaganda. They quickly called upon the most prominent French artist of that time, Jacques-Louis David, to immortalize Marat on canvas. David shared a close bond with Marat, for they both were friends since the revolution, and had both voted in favor for Louis XVI to be guillotined.

David was a neoclassicist, and would often look to the classical ideals of the Roman Republic in his artistic works. However, for painting Marat, he changed his tune – and decided to portray him as he was in the contemporary setting. Marat was shown as a classical hero (the details of Marat’s hand echo similarity with those of Jesus’ in Michelangelo’s Pieta) but not trivialized as such. There is only the bare minimum present in the field of view; Marat himself has been left in front of our eyes as a vulnerable, naked man who continued his service to the state even when he faced death.

For someone who famously painted classical themes (and their influences, for example in Napoleon Crossing the Alps), David’s art here resulted from the happenings in his society.

From the historical to the social

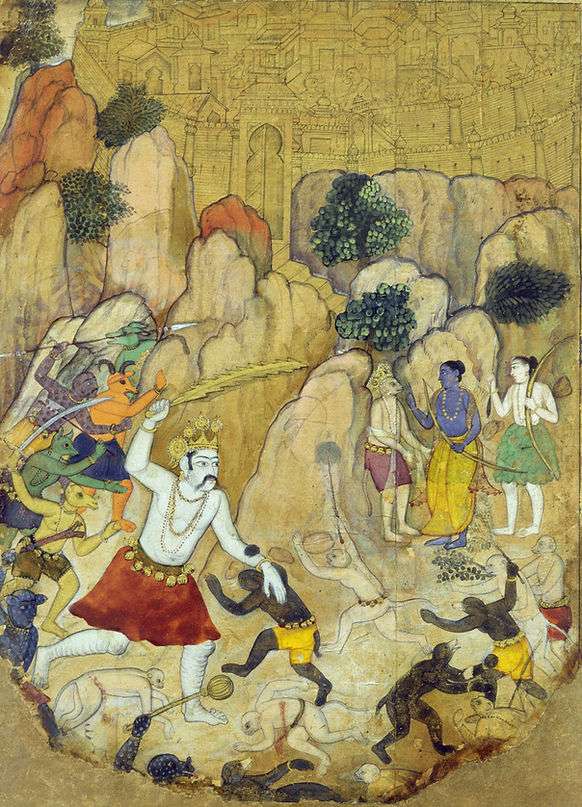

By the time the Mughal capital settled in Agra with Akbar, a more considerate attitude was adopted for Hindu subjects. This resulted in a clash between two of his courtiers – Abu’l Fazl and Badayuni. Fazl lauded Akbar’s attempts to assimilate the Rajputs and Badayuni rejected this appeasement.

Between these squabbles, however, emerged a culture of painting in Akbar’s atelier that would subsequently define art right till the era of Independence. Akbar was known to take an active interest in studying Sanskritic traditions, ordering translation of epics like Ramayana and Mahabharata into Persian, and commissioning their illustrations.

What this achieved was the establishment of a tradition where now social themes dominated the artist’s works. Where initially Mughal art was about legitimizing authority with royal symbols from Timurid traditions, art now became representative of the social milieu. This later trickled down into various regional art styles and subsequently, the basis of pre-independence oriental art.

Art then has been just as entrenched in the social, as it has been aesthetic. Especially in the seven decades of our independence, our socio-cultural realities have come to define what it is for art to be ‘Indian.’ Here then is a humble effort to highlight several moments in our contemporary history where changes in societal attitude resulted in the emergence of new ideas of art.

Global presence or an Indian absence?

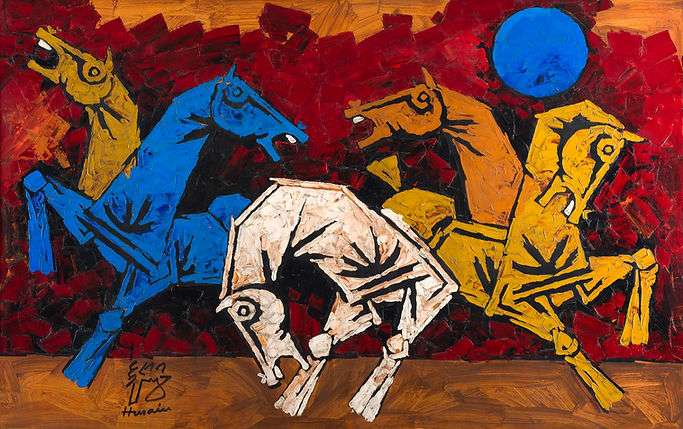

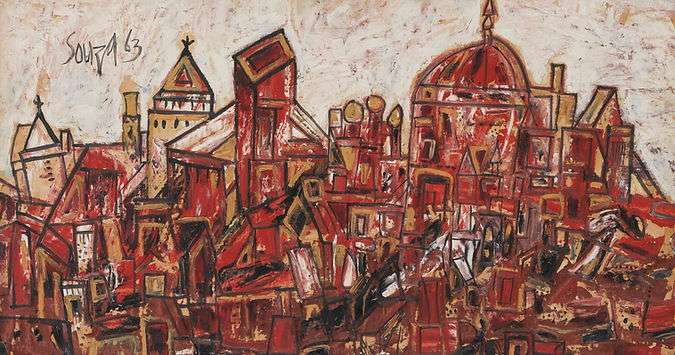

The Bengal school of art – which championed an oriental style of historical art – and the Bombay school of art – fighting for modern art – were the two leading thoughts that defined Indian art before independence, giving us artists like Jamini Roy and the Tagores. By the time India achieved independence, the Bombay school reigned supreme over Bengal, and on this backdrop, artists like FN Souza, MF Husain, SH Raza, and the Progressive Artists Group came together.

These artists faced a ‘burden’ of colonial India – Indian art till then was seen as artisanal and sought only under royal patronage. To break away from this stereotype, the PAG embraced modernism to assert themselves, but this proved not so easy. In front of the universal values of modern art, Indian values of iconography and decoration found a difficult space.

An orthodox communist ideology, that brought the PAG together also became another impediment. Issues of gender, caste, and ethnicity, which were hotly debated during those times didn’t fare against their ideas of class struggle. This, along with their individual avant-gardism meant that a relationship with the masses failed to take shape.

Stepping down from the high plinth

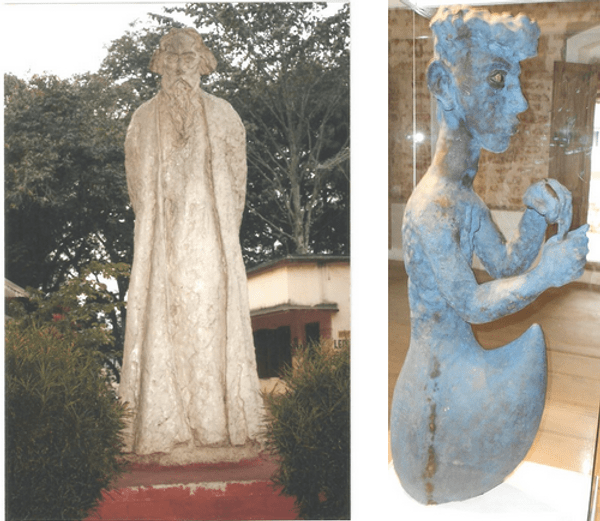

As if the country didn’t have enough problems, a catch-22 situation stopped the artists dead in their tracks: to get out of stereotypical notions, Indian artists now embraced the salon, gallery system of showcasing art. Yet this action led to them being more distanced from the common man. Notwithstanding the presence or absence of highbrow art, Indian artists effectively stood further away, further higher now. It was the Radical Group that leveled the field.

This group of sculptors and painters from Kerala in the 1980s was an extension of anti-cate, anti-feudal, and anti-establishment movements that erupted during the Emergency period in India. Left-leaning, these artists were upset with the growing capitalist tendencies in the art world. They shunned the commercial culture galleries were invested in and looked at providing art to the general public.

The Radicals began engaging more at a grassroots level where art camps were organized in public spaces to reflect the aspirations of the common people. Similarly, groups like SAHMAT and Open Circle produced artwork that touched notions of free speech, religious tolerance, and environmental and feminist demands. What these signaled were artistic notions of community and collaboration.

The fate of our furious times

A visual of a blood-splattered chappal and an iron rod at its side – what would one imagine happened there? It seems that it is the aftermath of a riotous situation, but we’re left to ask: what happened to the wearer of the chappal? And more chillingly, was the iron rod used to dispense the crowd or the person wearing the chappal?

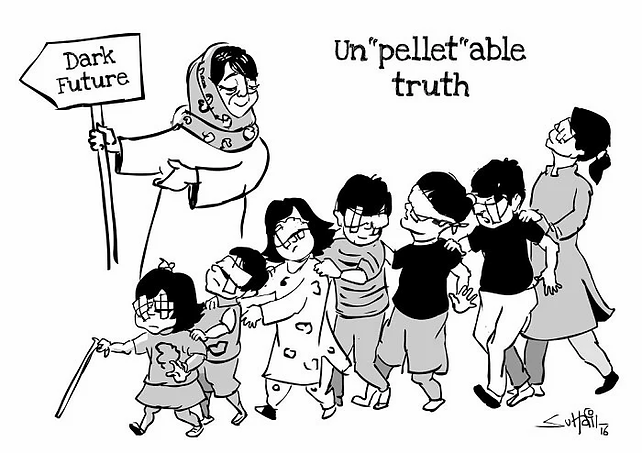

Orijit Sen’s poster for Not in My Name is just one example today of the environment in which Indian art has evolved from its predecessor of the 70s and 80s – with the growing tide of communal violence, Hindutva politics, and censorship of artistic freedom, new performance-based mediums are now employed to define how art in India is not “well-behaved” (Ranjit Hoskote) but a testament to the aspirations and sacrifices of the present youth.

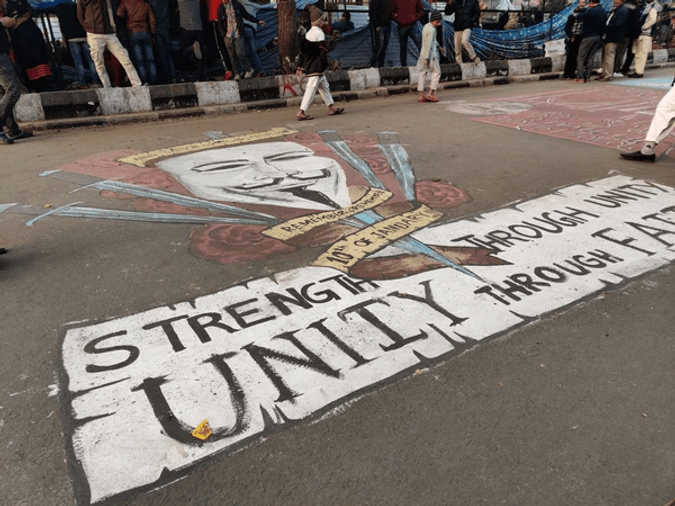

Several new mediums – most popularly digital art – has now meant that a new breed of political cartoonists has found flourish. Yet it is important to note that this is far from a democratic art practice – differences in caste and class won’t disappear at the touch of a button, and quite possibly then, the protest street art of the recent anti-CAA protests stands as a case in point of uniting people from all strata of society.

Women wearing cow masks and getting their pictures clicked in public – sounds like a bizarre tabloid headline, but is also the crux of Sujatro Ghosh’s work, where he highlights the societal beliefs in the sacred cow and continual violence against women in public spaces. While Ghosh’s work is just one example, this journey, from the studios of Abanindranath Tagore to the streets today, Indian art has been profoundly impacted by social changes. What this makes us realize then is that questions like who the art is for, and what is its immediate environment will always challenge the development of art practices in society.

While you’re here, make sure to check out our feature on revolutionary street artists and how they’re bringing societal issues to the fore with their graffiti, here!